| Bio-Bibliographical Guide to Medieval and Early Modern Jurists |

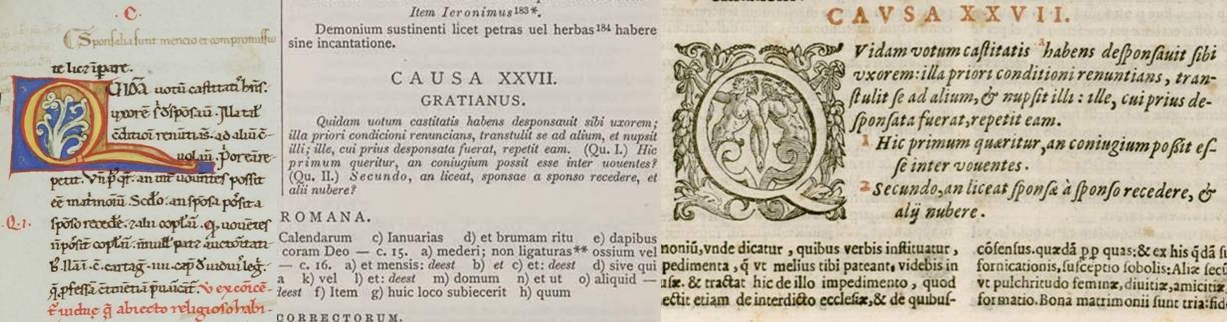

Click on image for more information |

|

Report No. t031 |

Cinus Sinibuldus Pistoriensis |

c. 1270–1336 |

|

| Alternative Names |

Cino, da Pistoia (LC); Cino Sinibuldi (Sighibuldi, Sigibuldi, Sigisbuldi) da Pistoia |

Biography/Description |

|

C. was a lawyer and a poet of the dolce stil novo movement, a friend of Dante, and a teacher of Bartolus de Saxoferrato. While there is some debate about the exact year of his birth, most sources indicate that he was born in 1270 into one of the most ancient and noble families of Pistoia. His father was Francesco di Guittoncino di Sigisbuldo and his mother Madonna Diamante di Bonaventura di Tonello. His surname is most commonly written as Sinibuldi, but other variants (Sighibuldi, Sigibuldi, Sigisbuldi) also appear, all derived from his ancestor Sigisbuldo, a consul of Pistoia in the twelfth century. In Pistoia, C. was taught grammar by Francesco da Colle. From 1292–1301, he studied civil law in Bologna under Dinus Mugellanus, whom he later remembered as dominus meus with admiration and affection. At Bologna, C. also studied under Franciscus Accursius, Lambertinus Ramponius, and Martinus Silimanis. Two Bolognese documents from 1297 and 1299 indicate that in those years he was licentiatus and planned to give, according to the university statutes, a lectura extraordinaria de sero. In the second half of 1302, he returned to Pistoia. Around this time, C. married Margherita di Lanfranco degli Ughi, who came from an old family that were partisans of the White Guelphs, though he himself was a partisan of the Black Guelphs. His association with the Black Gulephs led to his exile in 1303. He likely spent his exile first in Prato and then in Firenze, returning to Pistoia in April 1306. The next few years saw C. traveling widely throughout Northern Italy, meeting with Dante and other political figures. In 1310, when the future Emperor Henry VII moved to Italy, C. accompanied Ludovico di Savoia to Firenze. There, C. tried unsuccessfully to convince Ludovico to welcome Henry before he continued to Roma, where he probably remained until 1312. The following year, C. followed the emperor to Pisa where Henry died shortly afterwards. With the death of Henry, C. abandoned political activity and dedicated himself to drafting his lectura Codicis which he finished on 11 June 1314. During this time, he may have lived in Pistoia. It is certain, however, that in the second half of 1314, C. returned to Bologna where he successfully passed his exams and earned his degree on 9 December, 1314. From 1314–1321, C. served in various administrative offices. On 22 December, 1314, C. went to Siena where he took the oath to serve as a collateral judge for the Bolognese podestà, Bartolino da Sala. He served in this office for the first half of 1315, at the same time as Tancredus de Corneto. He served in Siena and also in Pistoia for the next several years, leaving behind a number of consilia. In 1319, C. went to the Marches, where he served as a papal official in Marcerata and Camerino until 1321. In 1321, he began the final phase of his career, working first in the studia of Siena until 1326, and then in Perugia and Napoli, while frequently serving as a consultant. In April 1324, C. would have met the young Petrarch in Bologna before travelling to Firenze to oversee the election of the podestà. In November 1326, C. was a professor at the studio in Perugia where he taught, among others, Bartolus de Saxoferrato. After this, he taught at Napoli in 1330–1331 and probably also for some months in 1331–1332 where he frequently met with Giovanni Boccaccio – though C. seems to have become uncomfortable in Napoli; he wrote a violent, satirical canzone against the Neapolitans. The first half of 1332 found C. in Firenze where he led discussions between the municipality of Pistoia and Simone Della Tosa, resulting in their reconciliation. From October 1332 to August 1333, he returned to teaching in Perugia. In his last few years, C. was elected to various positions in Pistoia, but he does not seem to have accepted them. On 23 December of 1336, C. drew up his testament. The document indicates that at this point he had attained the rank of a sapientissimus vir et elegantissimus iuris professor. His son Mino had predeceased him; C. appointed Mino’s son Francesco his universal heir, to whom he bequeathed his books, and he left legacies of different amounts to his wife and daughters Giovanna, Beatrice, Diamante, and Lombarduccia. A libellus concerning C's financial affairs, compiled by Schiatus de Lanfrancus Astesius, the husband of his daughter Giovanna and the curator of his testament, notes C’s date of death, 24 December [1336]. C’s heirs erected a funeral monument to him, still standing, in the cathedral of San Zeno in Pistoia. C. had a number of important connections with the Italian humanist and literary communities. According to C., Dante was the Italian poet of love par excellence. In addition to Dante, he was in contact with other poets and met Petrarch, who wrote a sonnet in his memory, and Boccaccio, who admired C. as a student, colleague, and teacher. C. himself wrote some vernacular poetry; he is also said to have written some verses in Latin, but no evidence of these has yet been found. C’s profession also connected him with the brightest stars of the legal world and with scholars of other disciplines, such as the physician Gentile da Foligno from whom he requested a well-known technical opinion on the duration of pregnancies. C’s legal works include a number of lecturae, glossae, additiones, quaestiones, and consilia. His glossae contrariae, explaining the magna glossa, were the work of his youth. The lectura Codicis, published in 1314, was an impressive commentary in which C. examined the doctrinal innovations of the moderns – that is, the masters of Orléans and in particular of Petrus de Bella Pertica, the teacher of C’s mentor, Dinus Mugellanus. C. continued to update this work with additiones which were incorporated into the text. This commentary was well received and is preserved in numerous manuscripts and many printed editions, the first of which dates from 1475 and the last of which appeared in Frankfurt in 1578, published by Nicolaus Cisnerus. C. wrote extensively about the Digestum vetus. The beginning of a lectura (Dig. 1.1–2.9) is known in three manuscripts. It was printed in the 16th century, sometimes separately, sometimes together with the lectura Codicis. C’s De rebus creditis on Dig. 12.1 was frequently used by later jurists. Finally, C. wrote a divina ordinaria lectura on the Digestum vetus later in his life, the beginning of which is preserved in at least two manuscripts. This text was long misattributed to Bartolus, but Domenico Maffei proved that it is the work of C. We also know of a commentary on De iustitia et iure (Dig. 1.1.1) which is described as a proemium, but is not found in either version of the lectura on the Digestum vetus. It likely served as an inaugural lectio for an academic year. C. also left additiones and apostillae both on the first and, less extensively, on the second part of the Infortiatum as well as additiones on the Digestum novum. Several consilia survive in various manuscripts and archival documents, one of which is autographed, as do some quaestiones. The allegationes domini Cyni de Pistorio, however, preserved in the ed. Venezia 1608 of the consilia of Baldus, cannot be definitively ascribed to C. (They may be by Baldus’ contemporary Cino di Marco da Pistoia, a canonist, who is sometimes said to have been C’s nephew.) The authorship of the treatise De successione ab intestato (TUI 1584, 8.1.319rb) is even more uncertain. The attribution to C. is not corroborated by his usual stylistic traits and was already challenged by Diplovatatius, who traced it back to a certain “Dynus de Pistorio,” perhaps identifiable as the jurist Dinus Torsiglierus de Pistoria (Dino Torsiglieri da Pistoia). C’s lasting popularity is evidenced by the repeated references to, and uses of, his work: a Repertorium C. is found in a number of manuscripts; the Singularia C. de Pistorio which was written, according to Ciampi, by Antonius Minuccius; and finally the Ad C. Pistoriensem, additiones, et ad nunnullas leges Codicis, adnotationes published in 1602 in Napoli by the jurist Pompeius Battaglinus. P. Maffei (DGI 1:543-46) provides a helpful analysis of C’s work and methods, summarized briefly here: Although C. has often been thought of as the first Italian to have fully applied the French method of commentary, the situation is more complicated. While his commentaries approach the model of the Orleanese repetitio, more organic and elaborate than those of his immediate predecessors, C. did not entirely discard the traditional style. To explain his very wide knowledge of the Orleanese school, and in particular of Petrus de Bella Pertica, some have proposed that C. stayed for a time in France. This is unlikely; works generally circulated much more quickly than used to be imagined, and Angevin Napoli was a center of diffusion for transalpine scholarship. Moreover, C. himself tells us that in the year 1300 he heard a repetitio which Bella Pertica delivered in Bologna on his way to Rome. Not only was C’s debt to Bella Pertica universally recognized by his contemporaries, C. himself declared that he had written his monumental work on the Code precisely to open Bologna to Orleanese thought and methods. This does not mean, as some have suggested, that the jurist-poet’s work lacked originality. C. did not mechanically reproduce French thought, but submitted it to scrutiny – although it must be admitted that we do not yet know how much he relied for this upon his master, Dinus Mugellanus. In this, C’s commentary on the Code is a work that stands on its own. In his other works C’s personality is prominent, particularly in the fragment of the divina ordinaria lectura Digesti veteris (discovered by D. Maffei), which demonstrates an unusual capacity for independent and systematic elaboration. C’s initial engagement with politics was, like Dante’s, encouraged by the rise of the emperor Henry VII – but Henry’s death extinguished C’s enthusiasm and passion for politics. Nonetheless, C’s examinations of the Donation of Constantine throughout his life allowed him to maintain an interest in the topic. A convinced opponent of papal power and proponent of imperial supremacy for most of his life, around 1330, he reconciled himself with the Angevin Guelphs in his lectura Digesti veteris. Here, C. abandoned the dualistic Orleanese theories and, adhering to the hierocratic positions of Dinus, maintained that the Church was the greater of the two powers, both in its nobility and origin, while also arguing for the legitimacy of the Donation. C. was driven to this stance when the hated “oppressor,” Louis IV, succeeded Henry VII. At the same time, papal supremacy appeared less dangerous to Italian liberties as the popes continued to reside in Avignon. C’s final positions on the Donation also circulated in the form of additio, the text of which, at least that of the ms. Bibl. Communale Mantua, 253, aligns, except for formal differences, with that of the lectura Digesti veteris. |

|

Source: P. Maffei, DGI 1.543–546. |

Entry by: CD/DC, rev CD/MBC/RO/DJ viii.2023 |

Text(s) |

| No. 00 | Note. We confine ourselves here to C’s legal works, omitting his poetry. So far as we are aware, there is no comprensive acount of the latter, but the editions and the literature are listed by S. Carrai and P. Maffei in DBI. |

| No. 01 | Commentaria in Codicem, 1314, with later additions. Most of the additions seem to be incorporated in the printed eds. Lange/Kriechbaum, Kommentatoren, 640–647 present in parallel examples of C’s text compared with that of Petrus de Bella Pertica. |

| No. 02 | Lectura in Digestum vetus. Incomplete in what survives. D. Maffei discovered that there is a second recension of the lectura, called divina ordinaria lectura, different from the printed editions. He detected in the latter recension a change in C’s attitude toward the Donation of Constantine. |

| No. 03 | Additiones. On all parts of the Corpus Iuris Civilis and on a few on parts of the Corpus Iuris Canonici. |

| No. 04 | Glossae contrariae. A work of C’s youth. |

| No. 05 | Distinctiones. A few, only in manuscipt. |

| No. 06 | Repetitiones. A few, only in manuscipt. |

| No. 07 | Quaestiones. Distinguishing between consilia and quaestiones is not always easy, particularly because manuscript cataloguers have a tendency to attach one or the other label without examining the contents of the item carefully. ‘Rector civitatis’, for example, may have begun as a consilium. It certainly became a quaestio. (Whether it was ever publicly disputed is a different question.) ‘An civitas possit tollere iurisdictionem Castri Pergulae’ may or may not have been a consilium to start off with. We have our doubts. |

| No. 08 | Consilia. A number of the articles in Literature that deal with C’s consilia also have full or partial editions. We have not listed these under Modern Editions, but refer to the literature in our accounts of the manuscripts. |

| No. 09 | Tractatus De successione ab intestato. P. Maffei in DGI notes that Diplovatatius questioned the attribution and ascribed the work to a Dinus Pistoriensis, perhaps Dinus Torsiglierus de Pistoria (Dino Torsiglieri da Pistoia), a jurist who lived in the second half of the 14th century and into the 15th. V. Capponi, Biografia pistoiese (Pistoia 1878) 379–380 online). P. Maffei shares Diplovatatius’ doubts, noting that the style of the work is unlike anything else that C. wrote. Dolezalek lists three manuscripts without questioning the attribution, but the attribution may be that of manuscript cataloguers rather than of the manuscript itself. The incunabula that we have been able to examine do not seem to attribute the work to C. For what may be the first time that the work is ascribed to C., see under Early Printed Editions, Tractatus (Lyon 1549). |

| No. 10 | Works by others summarizing or incorporating C’s work. |

Text(s) – Manuscripts |

| No. 00 |

Note. |

| Manuscript | This listing of manuscripts is derived for the most part from Dolezalek’s Manuscripta juridica. Additional citations or corrections from the online catalogue of manuscripts of the BAV (DVL) or from Mirabile are noted. We have explored more recent catalogues of other libraries only selectively. |

| No. 01 |

Commentaria in Codicem, 1314, with later additions. |

| Manuscript | Dolezalek lists 49 mss of the Commentary on the Codex, some partial, some complete. We list below those that from the Dolezalek catalogue seem to be complete, to antedate 1400, and to be in loci non ignoti. BAV (DVL) reports that Urb. lat. 174 is glossed. Many others probably are too. |

Cambrai, BM 630 |

Cambrai, BM 650 |

Cambridge, Peterhouse Coll. 5 |

| No. 03 |

Additiones. |

| Manuscript | Dolezalek lists six manuscripts that contain C’s additiones to the Digestum vetus, ten that contain his additiones to the Infortiatum, eleven that contain his additiones to the Digestum novum, thirty that contain his additiones to the Codex, four that contain his additiones to the Tres Libri, two that contain his additiones to the L.F., one that contains his additiones to the Volumen, and one that contains his additiones to Azo’s Summa Codicis. In most of these manuscripts C’s additiones are joined with those of others’; in a few he seems to be alone. Those in BAV (DVL) sometimes have more precise references. Catalogued to date are Barb. lat. 1460 (Infortiatum), Barb. lat. 1462 (Codex), Pal. lat. 629 (Liber extra), Pal. lat. 733 (Digestum vetus), Pal. lat. 736 (Digestum vetus), Pal. lat. 743 (Infortiatum), Pal. lat 757 (Codex), Pal. lat. 761 (Codex), Reg. lat. 1120 (Codex), Ross. 582 (Codex), Ross. 584 (Institutes), Urb. lat. 166 (Infortiatum). Mirabile lists six, including a Digestum novum, a Novels, and three canonical manuscripts. Of this large collection, we list those in Mirabile from CODEX, an inventory of Tuscan manuscripts; one in CALMA that seems to be somewhat misdescribed, and one cited by P. Maffei in DGI. |

| No. 08 |

Consilia. |

| Manuscript | Dolezalek lists 16 manuscripts that contain consilia of C., most in large collections with multiple authors. We list here those in which the description specifically mentions C. |

Bologna, Coll. Spagna 70 (no. 174) (Catalogued as ‘Tractatus de forma libelli contra sententiam’, from the incipit it clearly seems to be a consilium.) |

Firenze, Bibl. Marucell. C 393 (Letter of the famous physician Gentili da Foligno to C., perhaps concerning the latter’s consilium ‘De legitimitate pueri post septem menses nati’. Ed. H. Kantorowicz, ‘Cino’ from this manuscript. BAV [DVL] reports that another copy of Foligno’s letter is found in Vat. lat. 2289, fol. 277r–v, title De partu; incipit: Vir egregie domine Cyne ecce quid quaeris. BAV [DVL] also reports yet another copy made in 1502 by a doctor in Vat. lat. 8690, fol. 150r–151r, title: Tractatus super lege VII mense de statu hominum; incipit as above. P. Maffei reports in DGI that another copy is found MS Savigny 22 (above, under Digestum vetus). These copies would suggest that the letter is not to be connected with a consilium of C’s, as is normally thought, but with C’s lectura on Dig. 1.5.12, the lex ‘Septimo mense’.) |

Text(s) – Early Printed Editions |

| No. 01 |

Commentaria in Codicem, 1314, with later additions. |

| Early Printed Editions |

Lectura in Codicem - Pars 1. Strasbourg: Heinrich Eggestein, c. 1475 (GW 07045) (online). |

|

Lectura in Codicem - Pars 2. Strasbourg: Heinrich Eggestein, c. 1475 (GW 07045) (online). |

|

Lectura in Codicem - Pars 1. Pavia: Franciscus Giardengus, 1483 (GW 07046) (online). |

|

Lectura in Codicem - Pars 2. Pavia: Franciscus Giardengus, 1483 (GW 07046) (online). |

| No. 09 |

Tractatus De successione ab intestato. |

| Early Printed Editions |

Tractatus universi iuris: Tractatus compendiosus de successione ab intestato. Venezia: F. Ziletti, 1584, 8.1.319rb. |

Literature |

|

(This bibliography largely follows that in DGI. The bibliography in CALMA has more references to general works that mention C., and breaks up the entries by types of C’s works, but it misses a number of specific references that are in DGI.) |

|

S. Ferrilli, ‘Cino da Pistoia, Francesco da Barberino e l’astrologia giudiziaria: tra poesia, politica e cultura giuridica’, in Poesia e diritto nel Due e Trecento italiano, F. Meier, ed. (Memoria del tempo 65; Ravenna 2019) 105–124. |

|

S. Carrai and P. Maffei, ‘Sinibuldi, Cino’, DBI (2018) (online). |

|

P. Maffei, ‘Cino Sinibuldi da Pistoia’, DGI 1.543–546. |

|

G. Murano, Autographa I.1 Giuristi, giudici e notai (sec. XII–XVI med.) (Bologna 2012) 35–43. |

|

M. Bellomo, Quaestiones in iure civili disputatae. Didactica e prassi colta nel sistema del dirito comune fra Duecento e Trecento (Roma 2008) 244–245, 277–279, 299, 331, 481, 529, 605 et alii. |

|

M. Ascheri, ‘Cino da Pistoia giurista: le ragioni del successo’, in Atti del Convegno su Pistoia comunale nel contesto toscano ed europeo (secoli XII-XIV). Pistoia 12–14 maggio 2006, P. Gualtieri, ed. (Biblioteca storica pistoiese 15; Pistoia 2008) 211–222. |

|

G. Marrani, ‘Cinus Pistoriensis’, in CALMA (2008) 2.5.618–620 (Mirabile online by subscription). |

|

H. Lange and M. Kriechbaum, Kommentatoren 632–658. |

|

K. Bezemer, Cino da Pistoia nel VI centenario della morte (Frankfurt am Main 2005) ch. 2, and p. 154. |

|

G. Murano, Opere diffuse per exemplar e pecia (Turnhout 2005) 177, 333–335. |

|

A. Pérez Martín, ‘Cino de Pistoya’, in Juristas universales (2004) 1.323–326 (online). |

|

M. Conetti, L’origine del potere legittimo. Spunti polemici contro la Donazione di Costantino da Graziano a Lorenzo Valla (Parma 2003) 99–105, 112–117. |

|

K. Bezemer, ‘Word for word (or not). On the track of the Orleans sources of Cinus’ lecture on the Code’, TRG, 68 (2000) 433–454. |

|

K. Bezemer, ‘“Ne res exeat de genere” or How a French Custom Was lntroduced into the “ius comune”’, RIDC, 11 (2000) 67–115, esp. 99–101. |

|

D. Maffei, ‘Il pensiero di Cino da Pistoia sulla Donazione di Costantino, le sue fonti e il dissenso finale da Dante’, in Die Bedeutung der Wörter. Studien zur europäischen Rechtsgeschichte. Festschrift für Sten Gagnér zum 70. Geburtstag, M. Stolleis and others, ed. (München 1991) 237–247. Reprinted in: idem, Studi di storia delle università e della letteratura giuridica (Goldbach 1995). |

|

P. Nardi, ‘Contributo alla biografia di Federico Petrucci con notizie inedite su Cino da Pistoia e Tancredi da Corneto’, in Scritti di storia del diritto offerti dagli allievi a Domenico Maffei, M. Ascheri, ed. (Padova 1991) 165–168. |

|

A. Padovani, ‘The “Additiones et apostillae super secunda parte Infortiati” of Cinus de Pistoia’, in The Two Laws. Studies in Medieval Legal History Dedicated to Stephan Kuttner, L. Mayali and M. Früh, ed. (Washington, DC 1990) 151–165. (Originally appeared in SDHI 45 (1979) 178–244.) |

|

G. Savino, ‘L’eredità di messer Cino da Pistoia’, Atti e mem. Accad. toscana, 52 (Firenze 1987; repr. Firenze 2003) 103–40 . Reprinted in: idem, Dante e dintorni (Firenze 2003) 133–161. |

|

P. Falaschi, Ut vidimus in Marchia: divagazioni su Cino da Pistoia e il suo soggiorno nelle Marche (Napoli 1987). |

|

P. Weimar, ‘Cino, da Pistoia’, in LMA (1983) 2.col. 2089–2090 (Brepols online by subscription). |

|

M. Bellomo, ‘Cino edito e inedito in un manoscritto chigiano’, Quaderni catanesi di studi classici e Medievali , 4 (1982) 467–475. Reprinted in: idem, Inediti della giurisprudenza medievale, (Studien zur Europäischen Rechtsgeschichte 261; Frankfurt 2011) 183–190. |

|

Cino da Pistoia e la giurisprudenza del suo tempo (Atti dei convegni lincei 18; Roma 1976). Reprinted in: idem, Tradizione romanistica e civilità giuridica europea: Raccolta di scritti, G. Diurni, ed., 3 vols. (Ius nostrum 2a ser., 1; Napoli 1984) 1.371–403. (Except for the item listed immediately below, the other essays in this volume concern C’s poetry.) |

|

G. Astuti, ‘Cino da Pistoia e la giurisprudenza del suo tempo ’, in Colloquio Cino da Pistoia. Roma, 25 ottobre 1975 (Roma 1976) 129–53. |

|

W. M. Gordon, ‘Cinus and Pierre de Belleperche’, in Daube noster. Essays on Legal History for David Dauhe, A. Watson, ed. (Edinburgh-London 1974) 105–117. |

|

Cino da Pistoia. Mostra di documenti e libri. Biblioteca Comunale Forteguerriana di Pistoia, 30 settembre – 30 ottobre 1971, E. Altieri Magliozzi, ed. (Firenze 1971). (Document no. 14, p. 30–32, gives the date of C’s death.) |

|

M. Bellomo, ‘“Glossae contrariae” di Cino da Pistoia’, TRG, 38 (1970) 433–447. Reprinted in: idem, Inediti della giurisprudenza medievale (Studien zur Europäischen Rechtsgeschichte 261; Frankfurt 2011) 191–206. |

|

W. Bowsky, ‘A New Consilium of Cino da Pistoia (1324). Citizenship, Residence and Taxation’, Speculum, 42 (1967) 431–441 (JSTOR online by subscription). |

|

D. Maffei, La Donazione di Costantino nei giuristi medievali (Milano 1964; repr. Milano 1980) 135–141 . |

|

D. Maffei, La “Lectura super Digesto Veteri” di Cino da Pistoia. Studio sui mss. Savigny 22 e Urb. lat. 172 (Milano 1963). |

|

D. Maffei, ‘Cino da Pistoia e il “Constitutum Constantini”’, Annali della Facoltà giuridica, 24 (Napoli 1960) 95–115. |

|

E. Meijers, ‘L’université d’Orléans au XIII siècle’, in Études d’histoire du droit, R. Feenstra and H. Fischer, ed., 4 vols. (Leiden 1959) 3.120–121. |

|

G. M. Monti, Cino da Pistoia. Le quaestiones e i consilia (Orbis Romanus 13 [?14]; Milano 1942). (References to consilia edited in this work are given under Manuscripts.) |

|

G. M. Monti, ‘Altre indagini su Cino da Pistoia giurista e sulle sue “Quaestiones”’, in Cino da Pistoia nel VI centenario della morte (Pistoia 1937) 49–76 . Reprinted in: Studi in onore di Michele Barillari, 2 vols. in 5 parts (Annali del Seminario giuridico-economico dell’Università di Bari; Bari 1937) 2.4.21–63. (Monti [1942] is probably a reprint, combined with material from his thesis [1924]. It has 147 pp.) |

|

Cino da Pistoia nel VI centenario della morte, Comitato pistoiese per le onoranze ed. (Pistoia 1937). |

|

G. M. Monti, Cino da Pistoia giurista con una bibliografia e tre appendici di documenti inediti (Biblioteca di coltura letteraria 1; Città di Castello (Perugia) 1924). (This was Monti’s doctoral thesis.) |

|

G. Zaccagnini, Cino da Pistoia. Studio biografico (Pistoia 1918) (online). |

|

L. Chiappelli, Nuove richerce su Cino da Pistoia con testi inediti (Pistoia 1911) (online). Reprinted in: idem, Cino da Pistoia giurista: gli scritti del 1881 e del 1910–1911 (Pistoia 1999) (preface by D. Maffei, p. vii–ix). |

|

A. Mocci, La cultura giuridica di Cino da Pistoia (Sassari 1910). |

|

H. Kantorowicz, ‘Cino da Pistoia ed il primo trattato di medicina legale’, Archivio storico italiano, 37 (1906) 115–128 (online). Reprinted in: idem, Rechtshistorische Schriften , H. Coing and G. Immel, ed. (Freiburger Rechts- und Staatswissenschaftiche Abhandlungen 30; Karlsruhe 1970) 287–297. |

|

L. Chiappelli, Vita e opere giuridicbe di Cino da Pistoia con multi documenti inediti (Pistoia 1881; repr. Bologna 1978). Reprinted in: idem, Cino da Pistoia giurista: gli scritti del 1881 e del 1910–1911 (Pistoia 1999) (preface by D. Maffei, p. vii–ix). |

|

F. von Savigny, Geschichte 6.71–98. |

|

S. Ciampi, Vita e memorie di messer Cino da Pistoia, 2 vols., 3rd ed. (Pistoia 1826) (online). (On p. 71 we find the reference to Antonio Minucci’s Singularia Cini. Ciampi says that work is lost, though it is possible that it is included in Minucci’s printed works, many of which may be found in WorldCat, s.n. Antonio da Pratovecchio.) |