| Bio-Bibliographical Guide to Medieval and Early Modern Jurists |

Click on image for more information |

|

Report No. t028 |

Carolus Molinaeus |

1500–1566 |

|

| Alternative Names |

Du Moulin, Charles (LC); Charles Dumoulin; Charles Du Molin |

Biography/Description |

|

Son of an advocate in the Parlement of Paris, M. followed in his father’s footsteps. He studied law at Orléans, where he obtained his doctorate, and perhaps at Poitiers. He practiced at the Châtelet and then in the Parlement, but, though he distinguished himself as a jurist, he was less gifted for the bar because of a strong stammer. Pleading less, he went to sessions of the courts, gave consultations, and wrote. Around 1535, he began his first work, a commentary on the customs of Paris, the publication of the first part of which (On fiefs) in 1539 brought him fame. His need for money, however, obliged him to defer his commentary on the following titles in order to devote himself to works for pay: annotation of the works of the Italian jurists Philippus Decius, Alexander Tartagnus, and Dinus de Mugello. Later he composed a treatise on usurious contracts, rents, and money-changing, published in Latin in 1546 and summarized in French in 1547. In it, he took bold positions, favorable to unsecured rents (rentes volantes), loans for production (prêt à la production), and to monetary nominalism. 1546 also saw a Tractatus de eo quod interest on liability for damages and interest. Two short treatises on donations in the contract of marriage and ‘undutiful testaments’, prompted by a case in which he and his brother took opposite sides, appeared in 1551. To this period, too, belongs M’s important work on editing and annotating the Stilus supremae curiae parlamenti Parisiensis (1551). M. seems to have had an interest the law of the church – a subject that the onging Reformation made sensitive – from the very beginning. He is probably the anonymous author who contributed virulent annotations to the commentary of Dinus de Mugello on the De regulis iuris of the Liber Sextus in 1532 and 1535. His name appears on the editions of the same work in 1545 and 1548. Other than his work on Dinus, M’s work on canon law proper consists of notes on Decius’ commentary on the Decretals (1551), a commentary on the rules of the papal chancery (1552), and a large collection of notes on individual items in the Corpus Iuris Canonici that were gathered and published over the course of the seventeenth century. In 1551, M. published a commentary on the Édit des petites dates (Henry II, 1550). In it, he largely ignored the specific topic of the edict, the conferral of vacant benefices in the Roman curia, in order to engage in the conflict between Henry II and the pope. He advocated the withdrawal of obedience to the pope, which would permit the French church to organize itself as a national entity under the authority of the king, like the English church. The great impact of the work in France and abroad served the royal cause, but its author paid for it dearly. He was too naïve and too vain to understand that he was only a pawn in the hands of the king and of the constable of France, Anne de Montmorency. M. persisted in his attacks against the papacy, which exposed him to the suspicion of heresy and to condemnation by the Sorbonne. Compelled to flee in July 1552, he began a period of wandering in Protestant countries: at Basel, at Geneva (where he met Calvin), and at Lausanne, and then at Strasbourg, Marburg, Tübingen, and Montbéliard. Everywhere his prickly personality and his interventions in theological controversies set him at odds with the local authorities. They even earned him a brief stay in the jails of the count of Montbéliard. In the course of his forced exile, he belatedly became a professor, teaching in Strasbourg and Tübingen, without great success, because of his speech impediment. This new undertaking, however, led him to take a further interest in Roman law, which had become the common law of the Empire. He wrote commentaries on parts of the Digest and substantial parts of the Code, works on obligations, and a treatise on the Republican magistracies, which were, for the most part, published upon his return to France. M. came back to Paris in January 1557, after having stopped at Dole and at Besançon to give lectures. He then had five peaceful years, given profitably to the writing and publishing his works. The commentary on the second title of the customs of Paris (On censives) appeared in 1558 and a new, augmented edition of the commentary on the first title in 1560. He reedited the Commentaire de l’édit des petites dates and gave, under the title Traité de l’origine de la monarchie des Français, a revised version of the historical and political part of it. In 1561, he published his studies on contracts, the Nova et analytica explicatio rubricae et l. I. et II. de verborum obligationibus and the Extricatio labyrinthi dividui et individui, before plunging once again into civil and religious conflicts. M’s religion remains controversial. For a long time he was viewed as a zealous but versatile Christian, successively Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist, Lutheran again, and finally, in extremis, Catholic once more. Keen on theology, he was subject to the influence of new ideas and read the Lutheran theologians, Melanchthon and Bullinger. An ardent Gallican, he found himself in agreement with the anti-papalism of Luther on some points, but never adhered without reserve to the reformed dogmas, notably predestination. He probably remained an Erasmian, a moyenneur, open to multiple, and perhaps contradictory, influences, but he was always free in his judgment. He was so compromised in the eyes of the Catholics that he could not be rejected among the Protestants. He was a member of the council of the queen of Navarre; it was to the heads of the Calvinist party that he dedicated his works, and it was in the cities that they held, Orléans and Lyon, that he sought refuge at the outbreak of the wars of religion. He then broke with the Protestants and both camps became hostile to him. In 1563, Soubise, the reformed governor of Lyon, prosecuted him under the false accusation of having diffused subversive writings. In 1564, after his violent attacks against ‘the sect of the Jesuits’ in a piece written on the occasion of their trial at the university, it was the Parlement of Paris that imprisoned him for having published clandestinely his Conseil sur le fait du concile de Trente, in which he opposed the reception of the conciliar decisions. His Collatio et unio quatuor Evangelistarium, a work of theology that appeared in 1565, was condemned at once by both Catholics and Calvinists, but it was with the latter that he settled accounts by publishing works in which he denounced their plots against the royal authority and the increasingly authoritarian and centralized organization of their confession, and advocated for religious concord. M. died in December of 1566 disillusioned, leaving a large collection of short notes on the customs of France, the Notae solemnes, which assured his posthumous glory. They were published the year after his death in one of the first general coutumiers, Le Grand Coutumier contenant les coutumes générales et particulières du royaume de France et des Gaules, avec des annotations (1567), and they appear in many published editions of general customs until the eighteenth century, sometimes with the more critical of them removed. M. was a jurist in transition. His style, the construction of his works, his analytical and casuistic approach to the texts, his modes of reasoning, which identified in each question, arguments for and against, were those of a Bartolist faithful to the methods inherited from preceding centuries, but his broad learning, his open-mindedness, and his intellectual boldness were worthy of a humanist. For the most part, he wrote in the relatively simple Latin of the jurists with no pretense to elegance, but he knew Greek and even a bit of Hebrew. His dedications and orationes show that he was capable of more rhetorical Latin when he wanted to use it. His erudition was immense, and if history played only a minor role in his interpretation of Roman private law, where he remained attached to the letter of the laws and reserved with regard to the revolutionary methods of those of Cujas, it occupied a central place in his studies of French public law, which he founded on traditions going back to the origins of the monarchy. The contrast between his style and that of the humanists stems from the fact that he was a man of the early sixteenth century, of the generation prior to that of the great humanist jurists, and he remained a practitioner attentive to the specifics of each case, less drawn to abstractions and large theories. Immersed in the quotidian facts of the law, his treatises overflow with specific cases, concrete examples, practical advice. They offer neither grand syntheses nor systems and, compared with those of his successors, they appear disjointed. But, at bottom, M. showed himself an innovator, as the power of his spirit and his sharp sense of practice permitted him, in parting from traditional forms of reasoning, to arrive at original solutions. M’s contributions were considerable, and his influence was very important in the seventeenth century, when his Opera omnia were known in four editions (1612, 1624, 1658, 1681), and his Notae solemnes in six (1581, 1604, 1615, 1635, 1664, 1681). His influence waned, without disappearing, in the eighteenth century, when his works, having fallen out of fashion, were read only in French translations and synthetic abridgements made by Biarnoy de Merville and Henrione de Pansey, but they were mined by Pothier. His influence was also felt in Germany and in Italy, despite the relegation of many of his works to the Index in 1559. M. was one of the first to conceive, against the Bartolist dogma of the ius commune founded on Roman law, of the existence of a French law original in both its history and its contents, and to envisage its unification in the comparative study of customs. He developed this theme in his Oratio de concordia et unione consuetudinum Franciae at the end of his Tractatus commerciorum et usurarum (1546), summarized in French at the end of his Sommaire du Traité des usures. The Oratio was later included in the body of M’s work on customary law. M. was not hostile to feudalism, but he supported, and perhaps accelerated, the evolution of the law of things by rejecting the domination of feudo-vassalic relations in private law, by making the real prevail over the personal; by reinforcing the rights of the tenant in the land, considering those rights as truly proprietary, and by mitigating the obstacles that resulted from the prerogatives of feudal lords. His analysis of community property and the condition of the married woman recognized the strong authority of the husband but gave the wife solid guarantees. It contributed to fixing the law of patrimonial relations between husband and wife in the celebrated maxim, Uxor non est propria socia, sed speratur fore. On the subject of conflicts of customs, he moderated the Bartolist theory of statutes by giving a larger place for the will of the parties in the determination of the applicable law. On the basis of a very free interpretation of Roman law, he laid the groundwork for modern solutions on the subject of damages and interest, the effects of monetary exchanges on the execution of contracts, termination of contracts on account of nonperformance, the indivisibility of obligations, legal subrogation, and representation in solidarity. On these questions, the majority of his theses, taken up again by Pothier (not without changes), passed into the Code of 1804 and made M. one of the founders of French civil law. |

|

Source: J. L. Thireau, in DHJF 363–366, s.n. Du Moulin, Charles. |

Entry by: DJ/CD viii.2024 |

Text(s) |

| No. 00 | Note. The final edition of M’s Opera omnia (Paris 1681) is divided into five long volumes, two on Ius Gallicum, one on Ius Romanum, and two on Ius canonicum. There are some advantages to this arrangement, but it ends up by gathering under one heading works about French customary law and procedure with works that start from Roman law in order to argue for its application in France and gathering under one heading works about canon law more strictly speaking with works about French public law, works about theology, and polemical works about both. We ended up with six categories: (1) French customary and procedural law, (2) Treatises in the syle of the ius commune, (3) Commentaries on Roman law, (4) Commentaries on canon law, (5) French public law, theology, and polemical works, and (6) Consilia and consultations. In all cases, we tried to arrange the works in chronological order, with dates, where they are known, and to distinguish those works that were published in M’s lifetime from those that were compiled from his Nachlass. In all cases, we identify in the notes where the work is found in ed. 1681, if it is. |

| No. 01 | Customary Law and Procedure. |

| No. 01a | Notae in Commentaria Bartholomaei Chassensaei super consuetudinibus Burgundiae, 4 Kal. July (28 June) 1525. In 1681 Opera omnia, 2.1069–1115, edited by François Pinsson (1612–1691) (B. Basdevant-Gaudemet, in DHJF s.n. 817), for what is said to be the first time. The colophon is dated 28 June 1525, and if that is right, it is the earliest work of M’s that we have. He is already showing his later style; the annotations are critical of Barthélemy de Chasseneuz’s (c. 1480–1541) (C. Dugas de la Boissonny, in DHJF s.n. 235–236) commentary on the Burgundian customs. |

| No. 01b | Prima pars Commentariorum in consuetudines Parisienses, 1539. In 1681 Opera omnia, 1.1–666. The first part (on the title De feudis) of M’s commentary on the custom of Paris went through two editions in his lifetime, but even the first edition is very large (356 fols.). |

| No. 01c | Oratio de concordia et unione consuetudinum Franciae, 1546. In 1681 Opera omnia, 2.690–692. The Oratio first appears at the end of the Tractatus usuarum in 1546 (Text03a) and was reprinted with that work many times. A French summary appeared in the French version of the Tractatus in 1547 (Text03c) and was similarly reprinted. It was not, so far as we can tell, printed during M’s lifetime as a separate work. |

| No. 01d | Commentaria in consuetudinem Borboniensem, ?1550. In 1681 Opera omnia, 2.757–764, with the following note on the t.p.: ‘quae incoepit anno M. DL. et imperfecta reliquit, ut ipsemet testatur ad §. 302 hujus consuetudinis & epist. ad sinceros Iurisprudentiae studiosos mense Decemb. 1561. praevia ad extricationem labyrinthis 16. legum’. There does not appear to be any separate printing (WorldCat). The editors in 1681 do not claim that theirs is the first printing, but we have not traced how far back it appears in M’s collected works. |

| No. 01e | Stilus supremae curiae parlamenti Parisiensis, 1551. In 1681 Opera omnia the work occupies 282 pp. and is divided into seven parts: 1. P. Stilus Curiae Parlamenti in septem partes divisus 2.409–415; In primam Partem ejusdem Stili Parlamenti additiones Stephani Aufrerii 2.415–469; 2. P. lnstructiones Stili Parlamenti 2.470–486; 3. P. Ordinationes Regie Antiquae & Authenticae 2.487–538; 4. P. De Regibus et Privilegiis Regni Franciae 2.539–550; 5 P. Quaestiones Joannis Galli 2.551–632; 6. P. Tractatus de forma Arrestorum 2.633–657; 7. P. Arresta Parlamenti Parisiensis 2.658–679. The work is of composite authorship. The style itself (the beginning of part 1) was thought in M’s time to have semi-official status, but is, in fact, the work of Guillaume Du Breuil (c. 1280–1344/1345) (J. Krynen in DHJF s.n. 348–349). Étienne Aufréri (1458–1511), with whom we have dealt s.n. Stephanus Aufrerius, is responsible not only for what are called the additiones to part 1, but also for much, if not all, of parts 2–4. Jean Le Coq (c. 1340–1399) (K. Weidenfeld, in DHJF, s.n. 629–630) is responsible not only for part 6, but for much, if not all, of the rest of the work. Aufréri was a parlementaire of Toulouse, and he seems to have wanted to get that parlement to adopt Parisian procedure. How wide Du Breuil’s and Le Coq’s vision ran is less clear, but by the time we get to M. he may have been thinking of a form of Romano-canonical procedure for use in all the customary courts in France. When the work appeared in M’s Opera omnia in 1681, Colbert had already promulgated the Ordonnance sur la procédure civile (1667). |

| No. 01f | Secunda pars Commentariorum in consuetudines Parisienses, 1558. In 1681 Opera omnia, 1.667–831. The second part (on the title De censive et droicts seigneuriaulx) of M’s commentary on the custom of Paris is shorter than that on first (180 fols.). The 1681 Opera omnia has commentaries on the remaining titles, which it describes as commentarius posthumus: tit. 3 beginning on 1.832, tit. 4 1.844, tit. 5 1.848, tit. 6 1.854, tit. 7 1.857, tit. 8 1.864, tit. 9 1.866, tit. 10 1. 867, tit. 11 1.878, tit. 12 1.892, tit. 13 1. 899, tit. 14 1.906, tit. 15 1.912, tit. 16 1.915, tit. 17 1.926, tit. 18 1.931, ‘autres coutumes’ 1. 933–934. These are obviously not on the scale of the commentaries on tit. 1 and 2. We have not explored when they first begin to appear in the printed eds. |

| No. 01g | Paraphrase aux loix municipalles, et coustumes du comté et pays de Poictou, de nouueau reformées . . . Le tout composé par Nicolas Theueneau . . . Reueu, corrigé, et augmenté par le mesme Autheur, etc. Table et repertoire des matieres. Les annotations de M. du Moulin., 1565. Not in 1681 Opera omnia. There are a number of editions of customs of particular areas that are said to contain the notes of M. None of these is in the 1681 Opera omnia as such. Perhaps the editors thought that all these notes were in M’s Notae solemnes, and they may be. This item, however, appeared before the Notae solemnes, and the following item appeared in the same year. In both cases it seems likely that the printer’s source for the notes was other than the published Notae solemnes. As the sixteenth century goes on, it seems more likely that the notes in such publications derive from the Notae solemnes, but we cannot be sure, and the publication history does show the diffusion of M’s work among lawyers who did not necessarily have a copy of a coutumier général. With this in mind, we list below all the publications of particular customs prior to 1600 which are said to contain the work of M. We have probably missed some where the library cataloguer was not confident enough of the date of publication to fill in the date field. A more complete listing can be found in A. Gouron and O. Terrin, Bibliographie des coutumes. |

| No. 01h | Les coustumes du bailliage de Vitry en Petrois, redigées & homologuées par les trois estats, en l’an mil cinq cens & neuf, 1567. Not in 1681 Opera omnia. See the note on Text01g. |

| No. 01i | Notae solemnes ad consuetudines gallicas, 1567. In 1681 Opera omnia, 2.693–756. As noted in the Biography, these notes were published the year after M’s death in one of the first general coutumiers, Le Grand Coutumier contenant les coutumes générales et particulières du royaume de France et des Gaules, avec des annotations (1567), and they appear again, sometimes with the more critical of them removed, in works with similar titles in 1581, 1604, 1615, 1635, and 1664. |

| No. 01j | Le coustumier du pays et duché de Bourbonnois, avec le proces verbal. Corrigé & annoté de plusieurs decisions & arrests, 1572. Not in 1681 Opera omnia, as such. It may be the source of Text01d. |

| No. 01k | Coustumes du duché et bailliage de Chartres, comté de Dreux, Perche-Gouët et autres terres et seigneuries estans audict bailliage de Chartres et païs chartrain. Avec les doctes annotations et apostilles de Maistre Charles Du Moulin, 1578. Not in 1681 Opera omnia. See the note on Text01g. |

| No. 01l | Les coutumes anciennes de Lorryz : des bailliage et prevoste de Montargis, de Sainct Forgeau, Pays de Puysaye, Chastillõ sur Loing, & autres lieux ressortissans audict bailliage de Montargis, comté de Gyen, Sãcerre, duché de Nemours, ce qui est au pays de Gastinoys, Chastellenie de Chasteaulendon & autres lieux regiz & gouvernez par lesdictes coustumes, 1597. Not in 1681 Opera omnia. See the note on Text01g. |

| No. 01m | Coûtumes du pays et duché d’Anjou, conferées avec les coûtumes voisines, et corrigées sur l’ancien original manuscrit, 1598. Not in 1681 Opera omnia. See the note on Text01g. This text is said to have been edited by François Pinsson (see Text01a and Text04d). |

| No. 01n | Commentaire sur l’ordonnance du grand roy François, en l’année 1539, 1637. In the 1681 Opera omnia, 2.765–808. The first edition of this commentary on Francis I’s Ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts (1539) that we have been able to find is in 1637, so its place in the chronology of M’s works has not been determined, but it is probably early. |

| No. 01o | Notes sur les coutumes générales du pays et duché de Bourgongne, 1663. These notes do not seem to appear in printed editions of the customs of Burgundy until 1663 (WorldCat), so their place in the chronology of M’s works has not been determined, but they may be drawn from M’s unpublished commentary on Barthélemy de Chasseneuz (Text01a). They do not appear as such in the 1681 Opera omnia. |

| No. 02 | Roman Law. Separating M’s commentaries on Roman law from his works that make use of Roman law in order to influence French law is not easy. As the Biography notes, M. did his first work on Roman law fairly early in his career when he made annotations for pay in editions of juristic writings. During his exile, his work on Roman law became quite serious; the ius commune was nominally the law of the Empire. Much, though not all, of this work was published upon his return to France in 1557. Ultimately, it was to have considerable effect on French law, particularly that of contract. It was, however, written (and spoken, because much of it derives from lectures) in a broader context than that of France, so it seemed best to leave it all under the category ‘Roman law’ and put only those treatises written in a specifically French context in Texts03. |

| No. 02a | Notae ad Regulas iuris [Dig. 15.17] Philippi Decii, 1545. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.1019–1034. These notes were many times reprinted with Decius’ work. When we put this work together with Text02c, Text02e, and Text04b, it seems clear that M. engaged in rather large scheme to publish works of Philippus Decius. Whether this was M’s idea or that of his Lyon publishers is hard to know, but the fact that a number of different Lyon publishers were involved suggests that the idea may have been M’s. |

| No. 02b | Notae ad Consilia Alexandri Tartagni, 1549. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.879–1018. These notes were also reprinted many times with editions of Tartagni’s consilia. |

| No. 02c | Notae ad Consìlia Philippi Decii, 1556. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.753–830. Although these notes were published during M’s exile, they probably were prepared before he left. |

| No. 02d | Quinque lectiones Dolanae, 1557. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.387–422. This is the first item that we can be sure was written during M’s exile. The lectures were given at Dole in 1556, on his way home. |

| No. 02e | Notae in Commentaria Philippi Decii ad ff. Vetus et Cod., 1559. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.831–878. Although these notes were not published until after M’s return from exile, they may have been prepared before he left. |

| No. 02f | Novus Intellectus quinque legum, 1560. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.352–369. It also has Nova & Analytica Explicatio L. Commodissime, 3.370–377; L. Si ita facta, 3.378–381, and L. Si mater, 3.382–386, which are also included in the Quinque leges. |

| No. 02g | Nova explicatio Rubricae de verborum obligationibus, 1562. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.5–87. The t.p. of the first ed. says that this item is derived from lectures were given at Dole and Tübingen. |

| No. 02h | Extrictatio labyrinthi dividui et individui, 1562. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.89–185. |

| No. 02i | Extrictatio labyrinthi sexdecim legum, 1564. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.186–313. It also has Novus intellectus legis Si partem, 3.318–344, which is one of the Sexdecim leges; and Novus intellectus in § Finito, 3.345–349 and Novus & analyticus intellectus l. Si usufructus, 3.350–351, both of which are probably parts of the Sexdecim leges. |

| No. 02j | Novus Intellectus quatuor legum, 1564. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.318–344. In the 1564 ed. printed separately with the Sexdecim leges. |

| No. 02k | Commentarius in sex priores libros Codicis, 1604. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.547–752. Unlike M’s work on the Digest, which is commentaries on selected leges chosen for particular purposes, this looks like an attempt at a complete commentary in the style of Bartolus. It lacks the last three books, and also tends to lack titles toward the end of the first six books. Commented on are: Cod. 1.1, 3, 18–23, 43; Cod. 2.1, 3– 6, 10–11, 13–16, 18–22, 28, 54, 59; Cod. 3.1, 8–16, 27–40; Cod. 4.1–10, 12–35, 37–54, 58, 66; Cod. 5.1–13; Cod. 6.1–9, 20–26, 28–37, 42. It is possible that M. left this work behind in Germany. The editio princeps (Hannover 1604) suggests that it was the product of his lectures at Tübingen. |

| No. 02l | Explicatio l. Si totas [Cod. 3.29.5], 1681. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.482–489. The editors do not claim that this is the first printing. Where they have it placed suggests that it is part of, or related to, the Tractatus de usuris (Text03a), although the topic of the lex would fit better with the Tractatus de donationibus (Text03d). |

| No. 03 | Treatises on Private Law. |

| No. 03a | Tractatus commerciorum et usurarum: redituumque pecunia constitutorum et monetarum, 1546. In 1681 Opera omnia, 2.1–332. |

| No. 03b | Tractatus De eo quod interest, 1546. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.423–481. |

| No. 03c | Sommaire du livre analytique des contractz, usures, rentes constituées, interestz, & monnoyes, 1547. In 1681 Opera omnia, 2.333–408. |

| No. 03d | Tractatus de donationibus in contractu mattrimonii factis, 1551. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.499–527. |

| No. 03f | Tractatus de inofficiosis testamentis, donationibus & dotibus, 1551. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.528–542. |

| No. 03g | Arrest au profit de Maiftre Charles du Molin, 12 April 1551. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3:543–546. Tacked onto the end of the preceding item, this document shows M’s personal invovement in the issues discussed in the treatise. |

| No. 03h | Tractatus de tempore utili et continuo: ad appellandum & prosequendum, ac de continuatione dominii et possessionis de una in alteram personam, nec non aliis continuationibus iudiciariis, 1563. Not in 1681 Opera omnia, nor should it be. Some library catalogues (OCLC accession number: 475217308) list this work as if it were co-authored by Marco Antonio Bardi and M. It is entirely the work of Bardi, printed a number of times, with no suggestion that M. had anything to do with it. The reason for the confusion is that OCLC 475217308 also includes Gaspar Caballini’s Tractatus de evictionibus. Caballini was long thought to be a pseudonym for M. For the most part, he is not. The Tractatus de evictionibus is his. Caballini did lend his name as the author of M’s De eo quod interest (Text03b) in order to avoid the censors and get it published in Italy. See s.n. Gaspar Caballinus. |

| No. 04 | Canon Law. |

| No. 04a | Notae in Commentaria Dini Muxellani in Regulas iuris pontificii [VI 5.(13)], 1532. In 1681 Opera omnia, 5.291–296. The ‘doctor anonymous’ who contributed notes to editions of Dinus’ commentary in 1532 and 1535 has been identified by library cataloguers as M. (WorldCat). If that is right, this would be the earliest of his printed works. Copes of these prints are rare, and none seems to be online. M’s name appears on the t.p. in the editions of 1545 and 1548. By that time, he was better known. |

| No. 04b | Philippus Decius Super decretalibus. Quid his commentariis accesserit ultra praecedentes editiones indicat epistola Caroli Molinaei iureconsulti clarissimi proxime sequenti paginae adiecta, 1551. Probably in 1681 Opera omnia, 5.297–348. The 1681 version is described as Notae in Commentaria Philippi Decii ad Ius Pontificium, but the dedicatory epistle is dated in 1550, and the contents look as if they are confined to the Decius on the decretals, with M’s notes. |

| No. 04c | Commentarius in Regulas cancellariae, 1552. In 1681 Opera omnia, 5.1–180. M’s interest in procedure has not received as much scholarly attention as it deserves. This work first appeared a year after his edition of the Stilus of the parlement of Paris. After M’s death, Georges Louet (c. 1540–1608) wrote notes on M’s commentary. They were not printed until 1656, and appear in the 1681 Opera omnia, 5.181–290. |

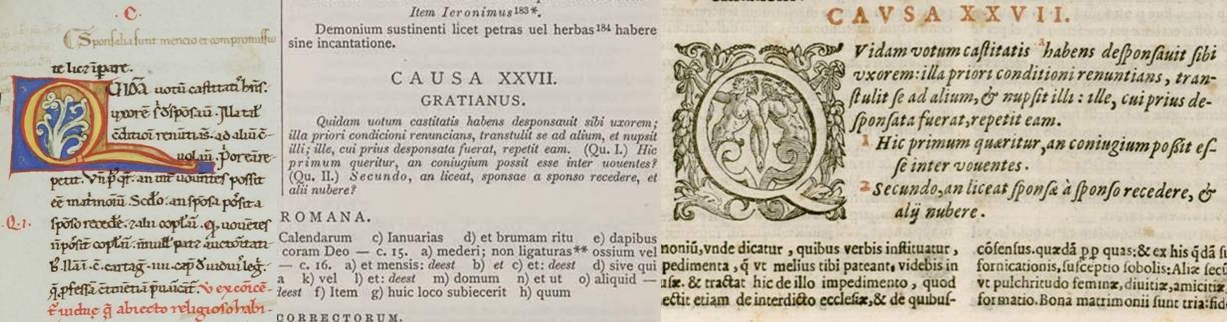

| No. 04d | Decretum Gratiani, 1559. Not in 1681 Opera omnia, but is said to be the source of the notes on Gratian in Text04e. The 1681 ed. cites another printing by the same publishers in 1553, which we have been unable to find. The 1559 ed. was reprinted in 1566. M. is said to have been the editor of Gratian’s text, as if he anticipated the work of the Correctores Romani, whose work was not published until 1582. However unlikely that seems, Text04e in the 1681 ed. suggests that that is what he did, at least in part. |

| No. 04e | Ad jus Pontificium seu Canonicum annotationes, 1603. Probably, at least in part, in Opera omnia, 4.1–294. The Danish Royal Library’s catalogue of the 1603 print (WorldCat) says that it includes: (a) Ad VI librum Decretalium annotationes, (b) Ad Clementinas annotationes, (c) Ad ius pontificium seu canonicum annotationes, (d) Ad Libros V Decretalium annotationes. Item (c) is presumably Gratian, or largely Gratian. The source of these items that an unknown editor put together in an unknown place is unclear. M’s notes on Decius on the decretals could be the source of some of what is in item (d). For another source, see the previous item. The 1681 edition claims that it is first publication and is entitled: Caroli Molinaei ad Ius Canonicum, et in easdem Gabrielis du Pineau et Francisci Pinssoniis adnotationes. Gabriel Dupineau (1573–1644) (S. Soleil, in DHJF s.n. 373–374) is a rather obscure jurist who otherwise wrote on the custom of Anjou. François Pinsson (1612–1691) (above, Text01a) is better known, and one of the things that he is known for is his participation in the 1681 ed. of M. The 1681 ed. covers all the parts of the Corpus Iuris Canonici, short notes that add up to something quite extensive. It seems to have been compiled over the course of the seventeenth century from M’s published works and perhaps from his Nachlass. There is no particular reason to doubt their genuineness. There is, however, as much, or more, of Dupineau and Pinsson than there is of M. in the 1681 ed. |

| No. 05 | Public Law, Theology, and Polemical Works. |

| No. 05a | Commentarius ad Edictum Henrici II contra parvas datas, 1551. In 1681 Opera omnia, 4.297–365. |

| No. 05b | Ad theologos Parisienses epistola cuiusdam iureconsulti, 1552. Not in 1681 Opera omnia. This 15 pp. item, printed in Basel in 1552, seems fairly obviously to be connected with the controversy that led to M’s exile. It is held only in the libraries of universities of Basel and Munich, neither of which has digitized it. It deserves more attention than it seems to have received. |

| No. 05c | Commentaire sur l’Edit des petites dates, 1554. In 1681 Opera omnia, 4.366–515. French translation of Text05a. |

| No. 05d | Solennis Oratio In Celeberrima Tubingensi Universitate Habita, De sacrae Theologi[a]e & legum Imperialium dignitate, differentia, convenientia, corruptione & restitutione: De potestate, officio & differentia Magistratus & ministri Ecclesiae, 4 K. March (26 Feb.) ?1554. In 1681 Opera omnia, 5.j–xiv, claimed to be the first printing. It is not. The lecture is dated 26 Feb. 1554, which, assuming a year that begins on 1 January, would fit a bit uneasily with the chronology of M’s travels. Perhaps we should be thinking of 26 Feb. 1555. |

| No. 05e | Sankt Petrus nie nicht zu Rom ein Bischoffe gewesen sei, 1555. Not in 1681 Opera omnia. So far as we can tell, the only source for this is in German in Eine vberaus nützliche Historien, wie zur zeit des H. Augustini, die Bepste mit dem VI. Carthaginensischem Concilio von jrem primat oder gewalt haben gestritten (1st ed. Magdeburg 1555). The principal work in this book is the noted Lutheran scholar Matthias Flacius’ (1520–1575) account of what he calls the sixth council of Carthage (probably the one now dated in 418–419 and called the sixteenth). Beginning at the verso of image 172 in the online edition, we find: ‘Beiveisung des hochgelerten Caroli Molinei eines Parisischen Jurists das S. Petrus nie nicht zu Rom ein Bischoffe gewesen sey’. There follow 28 pages (though the pages are small) of argument based on Scripture and Roman history supporting the proposition. German cataloguers have identified this passage as an extract from M’s Text04e. The only online copy that we have of this work is later, and the passage could have been edited out, but it is not there in what we have, and it is in an entirely different style from what we have. Text05a or Text05g are more likely possiblities, but we cannot find it there either. The argument is more like one that Flacius would have made, but it is not impossible for M. (The Latin version of Flacius’ work (Basel 1554) makes similar arguments, but does not ascribe them to M., and the arguments are not so tight as those found in Sankt Petrus.) Perhaps Flacius and M. corresponded. |

| No. 05f | Factum pour la justification du Traité contra parvas datas, 1558. In 1681 Opera omnia, 4.516. This looks like a pleading before the inquisitor at the Sorbonne. The date is hard to believe, but it is possible that the proceeding continued after M’s return from exile. The editors in 1681 do not claim that this is the first printing, but we have not found any previous prints. The 1681 Opera omnia continues with In Molinaeum pro pontifice maximo authore Remundo Rufo, 4.517–638, a defense of papal prerogatives against M. There is an ed. Paris 1553. We suspect that Remundus Rufus (Raymond Leroux, in LC) is a pseudonym, as is Franciscus Vilierius in the original edition (Geneva 1554) of Hotman’s reply, which follows: Francisci Hotmanni Vilierii De statu primitivae ecclesiae ad Remundum Rufum, 4.619–660. Then: Duplicatio Rufi in patronum Molinaei, 4. 661–694 and Johannis de Selva Tractatus de beneficio, 4.695–1026. There are two Jeans de Selve, brothers (P. Arrabeyre in DHJF, s.n. 923–924). This one is the less well known (fl. s16/1/4). The treatise appears first in 1509, again in 1514, and many times thereafter. Du Moulin, at some point, wrote notes on it, which appear in ed. Paris 1628 and are probably contained in the 1681 ed. All four works are claimed in 1681 to be original prints, but we know that three of them are not. The Factum, which is not so claimed, may be. |

| No. 05g | De la Monarchie des François, 1561. In 1681 Opera omnia, 4.1025–1050. French translation of the historical parts of Text05a. |

| No. 05h | Apologie de Maistre Charles du Moulin, 28 June 1563. In 1681 Opera omnia, 5.xv–xxii, claimed to be the first printing, and may well be. This is M’s defense against the charges brought against him by Soubise in Lyon, discussed in the Biography. |

| No. 05i | Conseil sur le fait du Concile de Trente, 1564. In 1681 Opera omnia, 5.347–364, claimed to be the first printing. It is not. |

| No. 05j | Consìlium super actis Concilii Tridentini, 1565. In 1681 Opera omnia, 5.365–393, claimed to be the first printing. It is not. This is followed by Réponse au Conseil donné par Charles du Molin sur la dissuuasion de la publicacion du Concile de Trente en France par Pierre Gregoire Tholosain, 5.395–444. For Pierre Grégoire (1540–1597), see D. Quaglioni, in DHJF 500–501. First, and so far as we can tell only previous, ed. 1594. Not mentioned in ed. 1681, but appearing almost immediately after M’s publication is Jodocus (Josse) Ravesteyn’s (ca. 1506–1570) (Wikipedia) ‘Oratio in qua confutat inanes cavillationes quorundam, et nominatim C. Molinaei, adversus authoritatem sacrosancti Concilii Tridentini’ (Louvain 1567). |

| No. 05k | Collatio et unio quatuor Evangelistarum domini nostri Jesu Christi, eorum serie et ordine, absque ulla confusione, permistione vel transpositione, servato: Cum brevibus eiusdem Annotationibus ad finem operis, 1565. In 1681 Opera omnia, 5.449–606, which claims to have added for the first time notes found in M’s manuscript. |

| No. 05l | Consilium super commodis et incommodis novae seu factitiae Religions Iesuitarum, 1604. In 1681 Opera omnia, 5.445–448. |

| No. 05m | De Monarchia Francorum, 1610. In 1681 Opera omnia, 4.1051–1070. Translation back into Latin of Text05g. There may be earlier prints than 1610, but that was the first that we could find. |

| No. 05n | Tractatus De dignitatibus, magistratibus & civibus romanis, 1681. In 1681 Opera omnia, 3.1035–1088, not claimed as the first printing, but we have been unable to find a separate print and have not pursued when it first appears in M’s collected works. |

| No. 05o | La défense de Messire Charles du Molin par M. Simon Challudre, 1681. In 1681 Opera omnia, 5.607–620, not claimed as the first printing, but we have been unable to find a separate print, and have not pursued when it first appears in M’s collected works. Simon Challudre is an anagram of Charles du Molin, and there is little doubt that M. is the author. See M. Bruening, Refusing 248 n. 154; cf. idem, 135 and n. 151. The work is sometimes called Against the Calumnies of the Calvinists in English. |

| No. 05p | Articles presentez par du Molin contre les ministres de la religion prétendü reformé de son temps, 1681. In 1681 Opera omnia, 5.621–624, not claimed as the first printing, but we have been unable to find a separate print, and have not pursued when it first appears in M’s collected works. This would seem to be part of the previous item. |

| No. 05q | Information faite a la requeste de du Molin de l’ordonnance de la court, [20 February 1565], 1681. In 1681 Opera omnia, 5.625–632, not claimed as the first printing, but we have been unable to find a separate print, and have not pursued when it first appears in M’s collected works. The edict of Rousillon (1564), art. 39, adopted 1 January as the date on which the year changed, so the year of grace, which seems to be that of the ordonnance and not of the Information, corresponds to our 1565. The proceedings in question were presumably interrupted by M’s terminal illness in 1566. |

| No. 06 | Consilia and consultations. The items with this heading that are related to the controversies found in Texts05 are placed there. One might do the same with Text06a, but M. does not seem to have been personally involved in the controversy, though it is clear where his sympathies lay. |

| No. 06a | Consilia quatuor seu propositiones errorum in causa illustrissimi principis do. Philippi landgravii Hessiae, comitis in Katzen-Elnbogen &c. contra comites a Nassau et principes Auriaci, et erronea et iniqua iudicia per eos tempore captivitatis praefati langravii in curia Caroli Austrasii obtenta, 1552. Not in 1681 Opera omnia. For Philip I (1504–1567), landgrave of Hesse, an early German Lutheran prince and among the most active, see Wikipedia. He was imprisoned by Charles V, amusingly here called ‘Carolus Austrasii’ in reference to his Belgian origins. The Consilia quatuor seems to have been printed only once previously, but a number of copies of it survive (11 in WorldCat). It seems unlikely that the 1681 editors did not know about it, and they may have omitted it for political reasons. |

| No. 06b | Consilium . . . in causa illustrissimi domini Martini ab Aragonia, ducis Villaeformosae, comitis Ripacurciae cum subscriptione plurium doctissimorum iurisconsultorum amplissimi togatorum ordinis eiusdem curiae [Parisiensis], 1559. In 1681 Opera omnia, 2.982–1004. The answer to the consilium of a Petrus de Ancharano, which appears in ed. 1560, also appears in ed. 1681. For Martín de Guerra y Aragón, duke of Villahermosa and count of Ribagorza, see Wikipedia. |

| No. 06c | Consilia et responsa iuris, 1561. In 1681 Opera omnia, 2.809–981. Sixty numbered consilia of varying lengths. They await analysis, but private law, particularly inheritance, seems to dominate with an occasional intermingling of ecclesiastical property. |

| No. 06d | Consultation de Paris pour la noblesse de Picardie, 1564. In 1681 Opera omnia, 5.xxiij–xxviij, claimed to be the first printing. It is not. Supports the right of the estates of Picardy to consent to the election of the bishop of Amiens. It is followed in ed. 1681 with extracts from M’s introduction to Text02a and from the dedicatory epistle of Text04b. |

| No. 06e | Consultations et pieces de Me Charles Du Molin extraties du de Iason, appartenant a Me Auguste Galand, qui avoit appartenus audit du Molin, 1681. In 1681 Opera omnia, 2.1020–1024. Two items, similar to much of Text06c. The difference between a ‘consultation’ and a ‘conseil’ seems to be that the former is less formal, and, at least in these cases, there is no evidence of ongoing litigation. These are not claimed to be original prints, but we have found no separate prior publication and have not explored who ‘de Iason’ and ‘M. Galand’ are. |

Literature |

|

T. Izbicki, ‘Charles Dumoulin’s Annotations in a Lyon Edition of the Decretum’, BMCL, 39 (2022) 181–189 (online). |

|

M. Bruening, Refusing to Kiss the Slipper: Opposition to Calvinism in the Francophone Reformation (New York 2021) passim, esp. ch. 7 (online). |

|

J.-L. Thireau, ‘Du Moulin, Charles’, in DHJF (2015) 363–366. |

|

J.-L. Thireau, ‘Une vision du droit public romain au XVIe siècle: le Tractatus analyticus de dignitatibus, magistratibus et civibus Romanis de Charles Du Moulin’, in Science politique et droit public dans les facultés de droit, J. Krynen and M. Stolleis, ed. (Studien zur europäischen Rechtsgeschichte 229; Frankfurt am Main 2008) 393–410 . |

|

A. Pau, ‘Charles Dumoulin (Charles Du Moulin; Molinaeus) (1500–1566)’, in Juristas universales, R. Domingo, ed. (Madrid 2004) 2.174–177 [p. 107–109 in PDF]. |

|

E. Roche, ‘Du Moulin (Charles)’, in Dictionnaire des lettres françaises: Le XVIe siècle, M. Simonin, ed. (Paris 2001) 433–434. (Not seen. This is a rev. ed., of a work that originally appeared in Paris, in 1951, in vol. 2 of the Dictionnaire, at 270–271. We have assumed that the author of the article remains the same, but that may not be the case.) |

|

O. Jochen, ‘DuMoulin (Molinaeus), Charles (1500–1566)’, in Juristen: Ein biographisches Lexikon, M. Stolleis, ed. (München 2001) 188–189. |

|

R. Savelli, ‘Da Venezia a Napoli: diffusione e censura delle opere di Du Moulin nel cinquecento italiano’, in Censura ecclesiastica e cultura politica in Italia tra cinquecento e seicento, Cristina Stango, ed. (Studi e testi (Fondazione Luigi Firpo) 16; Firenze 1999) 101–154. |

|

J.-L. Thireau, ‘Charles Du Moulin avocat’, Revue de la Société internationale de l’histoire de la profession d’avocat, 10 (1998) 9–27. |

|

T. Wanegffelen, Ni Rome ni Genève. Des fidèles entre deux chaires en France au XVIe siècle (Paris 1997) 133–147. |

|

R. Savelli, ‘Diritto romano e teologia riformata: Du Moulin di fronte al problema dell’interesse del denaro’, Materiali per una storia della cultura giuridica, 23 (1993) 291–324. |

|

J.-L. Thireau, ‘Le comparatisme et la naissance du droit français’, Revue d’histoire des facultés de droit et de la science juridique, 10–11 (1990) 153–191. |

|

R. Filhol, Aux alentours du droit coutumier. Articles et conférences du doyen René Filhol (Poitiers 1988) 229–239, 241–279, 313–321. (Articles and lectures relevant to M. at the pages cited.) |

|

J.-L. Thireau, ‘Aux origines des articles 1217 à 1225 du Code civil: l’Extricatio labyrinthi dividui et individui de Charles Du Moulin’, TRG (1983) 51–109. |

|

J.-L. Thireau, Charles Du Moulin (1500–1566). Étude sur les sources, la méthode, les idées politiques et économiques d’un jurist de la Renaissance (Travaux d'humanisme et Renaissance; Genève 1980). |

|

A. Gouron and Odile Terrin , Bibliographie des coutumes de France: éditions antérieures à la révolution (Travaux d’histoire éthico-politique 28; Genève 1975). |

|

D. R. Kelley, Foundations of Modern Historical Scholarship. Language, Law and History in the French Renaissance (New York 1970) passim. |

|

D. R. Kelley, ‘Fides Historiae: Charles Du Moulin and the Gallican view of History’, Traditio, 22 (1966) 347–402 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/27830814 online by subscription). |

|

M. Reulos, ‘Le jurisconsulte Charles Dumoulin en conflit avec les églises réformées de France’, Bulletin de la Société de l’histoire du protestantisme français, 100 (1954) 1–12 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/24290632 online by subscription). |

|

R. Filhol, ‘Dumoulin (Charles)’, in DDC, R. Naz, ed. (Paris 1953) 5.col. 41–67. Reprinted in: idem, Aux alentours. |

|

J. Carbonnier, ‘Dumoulin à Tubingue’, Revue génerale de droit, de la législation et de la jurisprudence (1936) 194–209 (online). |

|

A. Terrasson, Histoire de la jurisprudence romaine (Paris 1750) 455–459 (online). |