| Bio-Bibliographical Guide to Medieval and Early Modern Jurists |

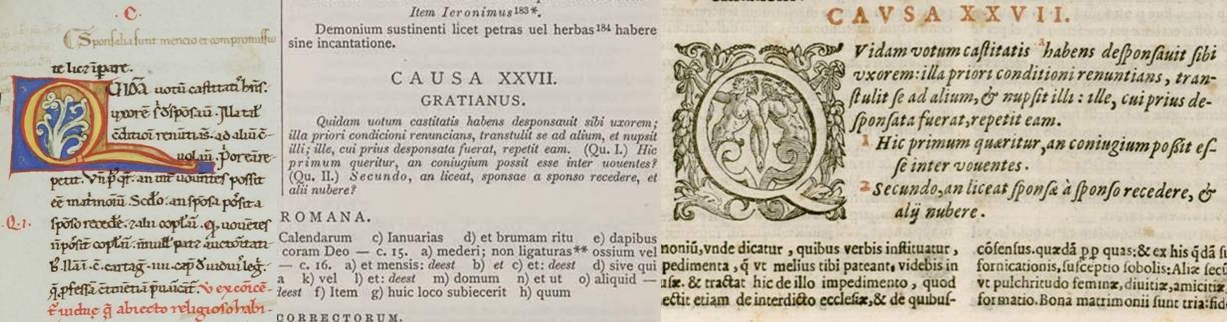

Click on image for more information |

|

Report No. c041 |

Johannes Faber |

c. 1275 – 1340 |

|

| Alternative Names |

Faure, Jean, -1340 (LC); Jean de Roussines; Jean de Montbron |

Biography/Description |

|

The life of Jean Faure, son of Étienne Faure, lord of Masmillaguet (Charente) and Almoïse of Salvaing, lady of Roussines, contains many gray areas. Having attended the university of Montpellier, then, it would seem, that of Bologna, where he may have obtained the doctorate, he became an advocate in Angoulème. For thirty years, however, he led a peripatetic life, perhaps in his capacity as seneschal of high justice for the barony of La Rochefoucauld in the Angoulème region. For the needs of his practice, he compiled, c. 1325–1330, a breviarium of Justinian’s Code, a kind of vade-mecum in which he tried to assemble the basic ideas of law. His second work, a commentary on the Institutes, compiled c. 1335–1340, was less cryptic than the breviarium, but responded to the same desire to create a practical work. He refused to spend time on the controversies of the doctors, which he thought tedious, but rather sought to find the common opinion. He tried to extract the rules of law, obscured, as he thought, by glosses and hidden in lacunose teaching. J. claimed to be a disciple of Jacobus de Ravanis and Petrus de Bella Pertica. He used Roman law to analyze the institutions and legal relations of his own time. Roman law thus offered him a context and tools to defend both lords’ jurisdiction against their rivals, the original power of the people in the election and creation of the prince, and the sovereignty of the king over his subjects, the feudal lords, the emperor, and the pope. He gave an important place to moral considerations, frequently citing the works of canonists, particularly Guillelmus Durandus, Johannes Monachus, and Johannes Andreae. If he often opted, in cases where the canonists and the civilians differed, for the civilian view, for example in the case of laesio enormis and nuda pacta, he did not hesitate on certain questions to privilege aequitas canonica over the rigor iuris civilis. He emphasized, for example, the principle of the transmissibility of penal actions against the heirs of the goods of the deceased, more than did either the lay or the ecclesiastical courts. The originality and force of J’s work lay, above all, in its constant confrontation of learned doctrine with French judicial and extrajudicial practices. He looked to the customs of the kingdom, and particularly the consuetudo regni Franciae, as well as the practice of the parlement of Paris. He used academic methods to analyze and criticize them both. He thus contributed to the birth of a French jurisprudence and of a French custom, in both private and public law. He systematized the immediate transmission, by the effect of seisin, of the rights and actions of the deceased to his successors and the principle of devolution of goods among heirs on the basis of their origin. The emergence of a rule of law by rational explanation of a usage also appears in his treatment of royal and seigneurial officers. His effort to strengthen the position of baillis by protecting them against arbitrary dismissal and affirming the continuity of their functions shows his constant desire to combat by law the abuses of the powerful. He raises to the level of a general custom of the realm the prohibition on imprisonment for civil debt except in the case where he debtor had specifically agreed to it. If he inclined to severity in the repression of crime, he was quick to denounce the corruption of judges and serjeants. Inclined, in the context of the revolt of 1314, to contain the power of feudal lords, he affirmed their submission to representatives of the crown and forbade them from acting in contempt of their subjects by levying new taxes, by appropriating to themselves roadways and water courses, or by transforming churches into fortresses. Reproaching the fines, seizures, and confiscations which the lord could impose on the goods of a vassal, he allowed release from feudal obligations by prescription and authorized royal judges to cite the parties where justice had been denied. The primacy of the idea of justice led him also to recognize the right of a subject to disobey a custom, a statute, or an order of the prince if it was contrary to the reason of natural law or to morality. He even admitted that the pope had the power to depose a king if the salvation of souls and the superior rights of justice were in peril. Cited by Italian and French jurists beginning in the second half of the fourteenth century, J. enjoyed an authority like that of the title falsely attributed to him, ‘chancellor of France’. From the end of the Middle Ages, French practitioners used him extensively, sometimes reinterpreting him, because his work was concrete and frequently contained concise formulations of doctrine. The commentary on the Institutes is known to have had five incunabulum editions and 22 in the 16th century. Its influence on the writers on customary law in the 16th and 17th centuries was considerable. The commentary on the Institutes was used by Barthélemy de Chasseneux in his commentary of the customs of Burgundy (first ed. 1517). Charles Du Moulin (on the title on fiefs, first ed. 1558) and Julien Brodeau (in the title on the retrait lignagier, first ed. 1658) used it in their commentaries on the custom of Paris. Jean Vigier, in his commentary on the custom of Angoulème (first ed. 1650), expresses great admiration for J. Nicolas Bohier in his commentary on the customs of Bourges (first ed. 1508) called him summus Franciae consuetudinarius. |

|

Source: K. Weidenfeld, in DHJF, s.n. ‘Jean Faure’. |

Entry by: CD v.2024. |

Text(s) |

| No. 01 | Breviarium Codicis, c. 1325–1330. |

| No. 02 | Commentarius in Institutiones, c. 1335–1340. |

Literature |

|

K. Weidenfeld, ‘Faure (Fabril) Jean (Jean de Roussines, Jean de Montbron), né vers 1275 à Roussines (Charente), mort en 1340 à Angoulème’, in DHJF, 2nd ed. (Paris 2015) 417–418. |

|

R. Feenstra, ‘Jean de Gradibus et ses éditions lyonnaises d’ouvrages de droit savant (fin XVe siècle – début XVIe siècle). L’example du commentaire sur les Institutes de Jean Faure’, in Mélanges en honneur d’Anne Lefebvre-Teillard, B. d’Alteroche and others, ed. (Paris 2009) 441–445. |

|

‘Faure (Jean)’, in Dictionnaire de biographie française, R. d’Amat, ed. (1975) col. 13.750. |

|

A.-J. Boyé, ‘Notes sur Jean Faure’, in Études d’histoire du droit offertes à Pierre Petot (Paris 1959) 27–38. |

|

P. Fournier, ‘Jean Faur, légiste’, in HLF (1920) 30.556–580 (online). (Fournier is at pains to correct what he deems to Savigny’s negative assessment of J.) |

|

H. Léridon, ‘Notice sur Jean Faure, jurisconsulte angmousin du XIVe siècle’, Bulletin de la Société archéologique et historique de la Charente, 4.3 (1865) 1–46 (online). (Prints, at 38–44, two charters from the A.D. Charente relevant to J’s family.) |

|

F. von Savigny, Geschichte (1850) 6.40–45 (online). |