| Bio-Bibliographical Guide to Medieval and Early Modern Jurists |

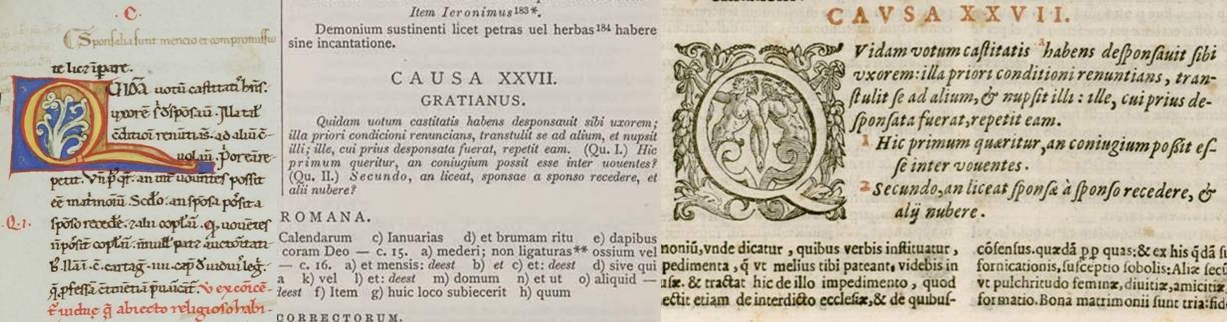

Click on image for more information |

|

Report No. c039 |

Accursius |

c. 1182 –a. ix.1262 |

|

| Alternative Names |

Accursius, glossator (LC); Accursius Florentinus; Franciscus Accursius ; Accursio; Accorso da Bagnolo; Accurse |

Biography/Description |

|

A’s given name was probably Franciscus, like that of his eldest son, but that is not completely certain. The date and place of his birth are also somewhat uncertain. The older accounts (Diplovatatius, Panciroli, Sarti–Fattorini, Savigny), based on traditions derived from Florentine chronicles (Filippo Villani, De origine civitatis Florentiae [14th century] and Domenico Bandini, Fons mirabilium universi) [early 15th century], derived in this part from Villani), give A. more than modest origins in the countryside of Florence and say that he was born in the early eighties of the twelfth century. Certainly he regarded himself as having come from Florence; the title Accursius florentinus occurs frequently in his great gloss. Contrary to the customary birth-place of Bagnolo, G. Speciale (‘Acursius’) has recently proposed that his roots lay in Certaldo. A’s personal and professional affairs are all linked to Bologna. He was a citizen there, served there as a miles, and was a member the Toschi, a society of arms of Bolognese citizens of Tuscan origin. According to late but reliable local annals, he arrived at the Studium, in 1218, the year in which the city’s Consiglio, called to the chair of letters Bene, a magister of grammar, even though he was a Florentine (G. Morelli, ‘Nuovi documenti’ at n. 29–30). Having received his intellectual formation in the schools of Azo and of Jacobus Balduini, with the latter of whom he may have received his doctorate (N. Sarti, Giurista 60–64; F. Soetermeer, ‘Doctor suus?’), he began to read in civil law in 1220 and taught for about forty years. The debates about his activities in his final years and about the precise date of his death are rehearsed by G. Morelli in DGI and in her ‘Nuovi documenti’. Suffice it to say here that the society of the Toschi gave notice that he was still alive in 1259 and a notarial act of May, 1263 refers to him as dead (P. Colliva, ‘Documenti’, nos. 9, 15). A recently discovered document has pushed the terminus ante quem back before 7 September 1262 (G. Morelli, ‘Nuovi documenti’ at n. 99) without quite confirming the traditional date of 1260. A. was buried in the city, first in the cloister of St. Dominic; then his body was taken to the apse of the basilica of St. Francis and placed in a marble sarcophagus made by his son Franciscus to house the mortal remains of them both. A. seems to have been married twice; certainly he had four sons, three of whom were domini legum: The first-born, Franciscus, is the most celebrated; Cervettus and Gulielmus are less well known; the youngest, Corsinus (fl. 1254 X 1272), practiced as a notary. A tradition of the 14th century attributed to A. a daughter who is said to have lectured on law (a possible echo of the similar story about Johannes Andreae’s daughter Novella). There is no contemporary evidence to support this tradition (P. Fiorelli in DBI). The fame and prestige that A. enjoyed allowed him to accumulate great riches. He records a number of immoveable properties in the great gloss (P. Colliva, ‘Documenti’ 456), including: a palatium, overlooking the Piazza Maggiore, and the ‘Riccardina’, which he called delectabilis nostra villa, and at which he constructed a church for the Franciscans and a convent, founded according to the will of the jurist (G. Morelli, ‘Nuovi documenti’ at n. 79). The putative contents of A’s library have given rise to a non-problem posed by H. Kantorowicz (‘Biblioteca’). On the basis of a document of 1273, which registers the sale of a collection of 73 codices (dogmatic works of civil and canon law, collections of feudal law, procedural treatises, etc.), by Cervettus to Guilielmus (P. Colliva, ‘Documenti’, no. 23), Kantorowicz posited that the catalogue of the sale proved A.’s intention, motivated by his experience in Florence in the last years of his life, to compile a juridical encyclopedia for use in the courtroom. The chain of conjectures that supports this hypothesis will not hold up. There is no evidence that Accursius was in Florence in the last years of his life (E. Genzmer ‘Lebensgeschichte’; P. Fiorelli, ‘Minima’). The catalogue plainly refers to publishing activity in which Guilielmus himself participated. Recent research confirms that the descendants of A. dedicated themselves to the ars mercadendie librorum (F. Soetermeer, ‘Utrumque ius’). What Cervettus sold to his brother were not the libri legales of their father, but exemplaria and peciae of the statio filiorum domini Acursi, where they did contract work until, for political reasons, they were forced to leave the city. A. and his son Franciscus were both accused of practicing usury in transactions with scholars. The history of the Bolognese Studium in this period shows that wealthy doctores often gave loans to students conditional on usurious interest (notably, Odofredus and his son Albertus). The persistence with which the accusation was made against A. can perhaps be traced back to the pro-imperial positions of the glossator and his son. It is probably not by chance, that the crime and sin of the two domini legum was absolved in a letter of Nicolas IV in 1291 (P. Collivi, ‘Documenti’, no. 25), at a point when the descendants of the master had all sworn fidelity to the pars Ecclesie et Jeremensium, the Bolognese faction that supported the pope. Thirteenth-century documents attest that notoriety in the city came to A. early. A document of 1221 speaks of a Donus, frater domini Accursii doctoris legum, rather than using the normal patronymic for Donus (G. Morelli, ‘Nuovi documenti’ at n. 35; cf. P. Colliva, ‘Documenti’, no. 1, for the same Donus similarly described in 1229). This is but the first reference to the jurist; numerous others, direct and indirect, follow. They prove A’s participation in Bolognese institutional life. The scholarly and didactic activity of A. were never separated from that of practice. Modern scholarship, beginning with P. Fiorelli (‘Minima’) and P. Colliva (‘Documenti’), has moved away from the image of A. as a theoretical exegete. His hermeneutic activity was oriented toward the Justinianic texts, in order to furnish them with a more complete and organic glossatorial apparatus than was then available. Thus, the imperial law could be applied to concrete needs and rendered intelligible and actualizable. A. felt the need to do so so acutely that he devoted almost his entire life to it. Up to the end of the fourth decade of the 13th century, A. worked toward a redaction of an apparatus to all the parts of the Corpus iuris. It is a monumental work. E. Seckel is said to have counted 96,260 glosses (P. Fiorelli in DBI). Not all of them, even those signed with his name, are actually A’s. The glosses are a work of undisputed scholarly as well as practical value. In his glosses, A. condenses a judicious selection of interpretations and doctrines of the jurists who preceded him, collating a vast body of material that he makes his own. He re-elaborates and enriches it with personal reflections, thus “closing the cycle of a unitary tradition” (G. Diurni, ‘Glossa’ 352). He liberates the manuscripts from the myriad glosses (interlinear and marginal), notabilia, allegationes, and distinctiones that had piled up alluvially in the available spaces of pages that handed down the sacred text of the leges. As G. Morelli in DGI desccribes it, A. thus furnished for the imperial sources an apparatus so clear in its language, so complete in its reference to parallel passages, so rich in its synthesis, that it became the Glossa magna or Glossa ordinaria, ‘the official gloss’. The work was recognized as an exceptional authority by the courts, hence the aphorism Quicquid non agnoscit glossa nec agnoscit forum. It accompanied virtually all of the manuscripts of the Corpus iuris and, from 1468 to 1627, the printed editions as well, except for Aloander’s editions of the Justinianic text alone (1529–1531) and a few like them. The diffusion of the ius commune in Europe ensured the reception of the great gloss as well. Recently, the great gloss has been described as ‘hypertextual’ (G. Speciale, Memoria 35–40). This was the root of its success. The glosses are united in a fragmentary, nonlinear structure, that has an inseparable, even physical, connection with the normative text. In the apparatus accursianus, all these elements are placed on the same hierarchical level, so that it is difficult to distinguish the more from the less important parts. By utilizing the tradition of the School, A. places the Justinianic text in a network of internal cross-references that orders and connects the various sedes materiae, giving the user a rapid, immediate and deep knowledge of the lex. There are, however, negative aspects of the great gloss. Modern scholarship recognizes the criticisms and reservations expressed by the humanists and the Scuola culta: the use of a technical language that was not that of the Roman jurists, errors in historical fact, and failure to place the text in its varying historical and institutional contexts. It also does not deny the occasional lacunae, contradictions, and errors that the additiones to the great gloss brought to light as soon as the second half of the 13th century. (There are, however, remarkably few outright contradictions. According to Dondorp and Schrage, Antonio Nicelli, in a work published in 1515, found only 121 in 96,240 glosses.) Modern scholarship also recognizes the risk of ‘disorientation’ and ‘cognitive overload’, caused by the vast quantity of information that the apparatus provides (a typical risk with hypertext). Morelli in DGI, nonetheless, regards Accursius as a precursor of the historical-critical method. The chronology of the redaction of the apparatus remains an obscure and perhaps an intractable question. Numerous studies have puzzled about the dating. The Digestum vetus can probably be placed around 1234, the Codex at the end of the 1230s. The work seems to have been compiled in successive moments, probably contextually, and some of the apparatuses may have had two complete redactions (Institutes: P. Torelli ‘Edizione’) (recent surveys: V. Valentini, ‘Ordine’; F. Soetermeer, ‘Ordre’; G. Diurni, ‘Glossa’). It is certain that the apparatus went through a phase of fluidity marked by various revisions, the fruit of continuous insertion of additiones, with which A. integrated, updated, or revised his previous writings, in order to coordinate his interpretations with the complete imperial Corpus iuris. Only in the course of the 1230s and 1240s did the work acquire the consolidated and crystallized form that triumphed over all the other preceding and contemporary apparatuses as the standard apparatus – a closed text canonized by the authority of its contents, and the final product of exegesis internal to the text, brought together in the printed editions. In the School in A’s time there was a current that resisted the dominance of A’s hermeneutic, sustaining and developing the pre-Accursian and pre-Azonian tradition (what M. Bellomo calls the ‘alternative line’ [‘Consulenze’, 200, and elsewhere]). Prominent among those who pursued this path were Jacobus Balduini († 1235) and Odofredus († 1265). As sources, A. privileged glosses of Azo, whose program “isolated the autonomous method of the jurist and vindicated its absolutely technical nature” (E. Cortese, Rinascimento 39), as well as those of Johannes Bassianus and Hugolinus Presbyteri. These sources are variously distributed in the various parts of the Corpus iuris and are rarely provided with the sigla necessary to establish their source. Most recently, H. Jakobs (Magna glossa) has suggested a method for determining how A. worked by looking at what seem to be manuscript survivals of the Azonian-Johannian apparatus, which he prefers to call the magnus apparatus in contradistinction to the Accursian apparatus, the glossa ordinaria. The many early manuscripts of the Accursian gloss are not all as deficient in sigla as are the printed editions. Work on these may give as a better idea of what lies behind the Accursian gloss. Other smaller works are included in the scholarly production of A., so much so that they cannot be considered independent of his work on the Corpus iuris: (1) Today the ordinary apparatus on the Libri feudorum is widely thought to be Accursian (P. Weimar, ‘Handschriften’; accepted most recently by A. Stella). It contains glosses that bear the siglum of Jacobus Columbi, q.v. for the literature, and may have been a reworking of Columbi’s apparatus. (2) Scholarship remains divided concerning the Summa on the LF. Seckel and Gualazzini assigned it to Columbi, but recently P. Weimar (‘Handschriften’) claimed it for A. (3) A Summa Authenticorum, by Johannes Bassianus has long been known to have had additiones made by A. (Savigny, 4.295–297; Kantorowicz, ‘Quaestiones disputatae’ 62–63, repr. 182). It has recently been argued that A’s additiones are an original work, perhaps a youthful one, separate from Johannes’ (F. Martino, ‘Summa’; G. Speciale, Memoria 83 and n. 12). (4) The manuscripts of the great gloss provide a series of quaestiones, additiones, and consilia of various kinds that ought to be considered as part of the larger work. A. supplemented his doctrinal and didactic work (see one of his teaching texts in G. Gualandi, ‘Episodio’) with professional texts of practice that explain, above all, the activity of counseling in the service of the Commune and of other institutions. The consilium sapientis iudiciale that gave the magistrate a guarantee of the legality of the proceedings is among the duties that civic legislation binds on a doctor legum (E. Cortese, Rinascimento 46–47). Such a function is attested by ten ‘professional’ consilia dated between 1234 and 1256 (P. Colliva, ‘Documenti’; Morelli, ‘Nuovi documenti’). Examples of ‘doctrinal’ consilia are in P. Colliva and M. Bellomo. |

|

Source: G. Morelli, in DGI 1.6–9; for more references, see her ‘Nuovi documenti’. |

Entry by: CD/DJ vi.2023 |

Text(s) |

| No. 00 | All texts. The problems with the attribution of some of these texts are discussed in the Biography.. |

| No. 01 | Apparatus ad Digesum vetus. |

| No. 02 | Apparatus ad Infortiatum. |

| No. 03 | Apparatus ad Digesum novum. |

| No. 04 | Apparatus ad Codicem. |

| No. 05 | Apparatus ad Institutiones. |

| No. 06 | Apparatus ad Tres Libros. |

| No. 07 | Apparatus ad Authentica. |

| No. 08 | Apparatus ad Libros feudorum. |

| No. 09 | Summa Authenticorum. |

| No. 10 | Summa Librorum feudorum. |

| No. 11 | Consilia. |

Text(s) – Manuscripts |

| No. 00 |

All texts. |

| Manuscript | Dolezalek’s, Manuscripta juridica lists over 1900 manuscripts that contain all or part of the Accursian apparatus. We list below two recent attempts at selectivity that emphasize earlier manuscripts that may contain clues as to how A. compiled his apparatus. |

| No. 01 |

Apparatus ad Digesum vetus. |

| Manuscript | H. Jakobs in Magna Glossa (298–301) compiled a list of surviving manuscripts of the Digestum vetus with the Accursian gloss, 224 in all, a reduction, as he explains (22 n. 22), from what can be found in Dolezalek, Manuscripta juridica. In ‘Irnerius’ Sigle’ (449–450), he lists 44 such manuscripts that are particularly early or particularly rich in sigla. We reproduce that list here, with the dates from Dolezalek where he has them, correcting occasional errors in the process. |

Arras, BM 586 (ex 497) (s. 13. The self-mark in Jakobs, ‘Irnerius’ Sigle’ is mistaken; it is correct in his Magna Glossa.) |

Bamberg, Staatsbibl. Jur. 13 (ex D.II.1) (s. 14) |

Basel, Universitätsbibl. C I 4 (s. 13. Dolezalek notes that a later hand has put in sigla: ‘m ’ ‘p ’ ‘y ’ ‘yr ’ ‘az ’.) |

Bernkastel-Kues, Bibl. St. Nikolaus Hospitals 280 (s. 13 or 14) |

Barcelona, Arch. Corona Aragón 281 (s. 13 or 14) |

Bruxelles/Brussel, Bibl. Royale 5671 (s. 14) |

Bruxelles/Brussel, Bibl. Royale 19119 (s. 14/1) |

Darmstadt, Landesbibl. 743 (s. 13. The self-mark is not given in Jakobs, ‘Irnerius’ Sigle’; it is mistaken in his Magna Glossa.) |

Douai, BM 575 (s. 13) |

Göttingen, Niedersächsische Staats- u. Universitätsbibl. 2° Cod.ms.jurid. 23 (s. 14) |

Firenze, Bibl. Laurenz. Acquisti 417 (s. 13/1) |

Firenze, Bibl. Laurenz. Acquisti 158.1 (s. 14) |

København, Kongelige Bibl. Gl.Kgl.Sml. 394 2°, pars I (s. 13) |

København, Kongelige Bibl. Thott 326 2° (s. 13) |

Leiden, Bibl. Rijksuniv. B.P.L. 6 C (s. 13/1) |

Madrid, BN 12080 (Undated. Not in Dolezalek or in the library’s catalogue, which has not yet reached this number. Jakobs confirms his discovery in Magna Glossa [300, and 22 n. 22].) |

München, BSB clm 14022 (s. 14) |

München, BSB clm 28176 (s. 13) |

München, BSB clm 3506 (s. 14) |

Paris, Bibl. Arsenal 693 (s. 13/2) |

Roma, Bibl. Casanatense 227 (s. 14) |

Roma, Bibl. Casanatense 28 (s. 14/1) |

Salisbury, Cath. Libr. 183 (s. 13) |

Stuttgart, Würtembergische Landesbibl. Cod. jur. 2° 72 (s. 14/in) |

Subiaco, Bibl. S. Scolastica XIV (s. 13) |

Toledo, Bibl. Catedral 32–2 (s. 13) |

Torino, BN Universitaria E I 1 (s. 14) |

Torino, BN Universitaria E I 11 (s. 14) |

Torino, BN Universitaria E I 15 (s. 14) |

Torino, BN Universitaria E I 22 (s. 13/1) |

Torino, BN Universitaria E I 23 (s. 14 or 15) |

Tübingen, Universitätsbibl. Mc 293 (s. 14/1) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 1409 (s.14) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 1410 (s.14) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 1411 (s.14) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 1412 (s.14) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 1413 (s. 13 or 14) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 2511 (s. 13/m) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 11155 (s.14) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Pal. lat. 739 (s. 14) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Pal. lat. 739 (s. 13 or 14) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Patetta 219 (Undated) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Reg. lat, 1121 (s. 13/ex) |

Vic, Mus. Episcopal 155 (s. 14. Not in Jakobs, Magna Glossa; his ‘Irnerius’ Sigle’ gives a shelf-mark that seems to be mistaken. This is the shelf-mark given in Dolezalek and in J. Laplante's Checklist [on12080line].) |

| No. 03 |

Apparatus ad Digesum novum. |

| Manuscript | A search for the title Digestum novum in Manuscripta Juridica returns 397 hits. Take out the the ones that are abbreviations, or just D.50.16 or just 50.17 or are uncertain, and we get 310. Then take out the ones that are fragmentary, and we get 202. Take out the 15 that are lost, destroyed, probable miscitations, or the present location of which is unknown, and we reach 187 at known locations. The list below includes only those that are available online. It does include the ones that contain pre-Accursian glosses, sometimes alone, sometimes in combination with the Accursian gloss. |

Carpentras, BM 200 (s. 13 [online (click on signature)]) |

Douai, BM 577 (s. 13 2d quarter [online]) |

Frankfurt am Main, Stadt- und Universitätsbibl. Barth. 15 (before 1336 [online]) |

Paris, Bibl. Sainte-Geneviève 395 (s. 13 [online]) |

Paris, BN lat. 4480 (s. 13 [digitized microfilm online]) |

Paris, BN lat. 4481 (s. 13 [digitized microfilm online]) |

Paris, BN lat. 4486 (s. 13 [digitized microfilm online]) |

Paris, BN lat. 4487 (s. 13/ex or 14/1 [digitized microfilm online]) |

Paris, BN lat. 14341 (s. 13 or 14 [online]. The BNF catalogue suggests a date before 1330.) |

Paris, BN lat. 16907 (before 1336 [online]. Contains pre-Accursian glosses.) |

Reims, BM 805 (s. 14 [digitized microfilm online]) |

Reims, BM 814 (s. 14 [digitized microfilm online]. Includes both Codex and Digestum novum.) |

Torino, BN Universitaria E.I.12 (s. 12/2 up to s. 14 [digitized microfilm online (click on signature)]. Contains pre-Accursian glosses.) |

Troyes, BM 130 (s. 13 [digitized microfilm online]) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Ott. lat. 3132 (s. 14/in [online]. A very large manuscript, contains all three parts of the Digest and the Code.) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Pal. lat. 747 (s. 14 [online]) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Pal. lat. 748 (s. 13/1 [online]. Contains Azo’s apparatus.) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Pal. lat. 749 (s. 14 [online]) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Pal. lat. 750 (s. 13 or 14 [online]) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Pal. lat. 751 (s. 13 [online]) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Pal. lat. 752 (s. 13 or 14 [online]) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Pal. lat. 753 (s. 13 [online]. Contains additiones by Dinus.) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Pal. lat. 754 (s. 12/1 [online]. Contains pre-Accursian glosses with the ordinaria added to an earlier base text.) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Pal. lat. 755 (s. 13 [online]) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Pal. lat. 756 (s. 12/ex [online]. Contains an apparatus from the time of Rogerius to which some of the ordinaria has later been added.) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Reg. lat. 1122 (s. 13 [online]) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Urb. lat. 163 (s. 14/ex [online]) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 1421 (s. 14 [online]. Described in published Kuttner, Catalogue.) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 1422 (s. 13/ex or 14/in [online]. According to the published Kuttner, Catalogue, contains many additiones.) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 1423 (s. 13 [online]. Described in the published Kuttner, Catalogue.) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 1424 (s. 13 or 14 [online]. According to the published Kuttner, Catalogue, contains many additiones.) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 1425 (s. 14 [online]. Described in the published Kuttner, Catalogue.) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 1426 (s. 14 [online]. Described in the published Kuttner, Catalogue.) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 9665 (s. 13 [online]. May be the apparatus of Hugolinus. According to the published Kuttner, Catalogue, contains many glosses with his siglum.) |

Città del Vaticano, BAV Vat. lat. 11156 (s. 12/2 or 13 [digitized microfilm online (click on signature on 5th page)]. According to the Kuttner, Catalogue proofs, may contain the apparatus of Rogerius.) |

Text(s) – Early Printed Editions |

| No. 00 |

All texts. |

| Early Printed Editions |

The Accursian gloss was printed with the base text early and often. GW lists 189 incunabula of parts of the Corpus iuris that contain the Accursian gloss: 78 of the Institutes, 24 of the Digestum vetus, 26 of the Infortiatum, 23 of the Digestum novum, 31 of the Codex, and 9 of the Novels. A number of the last-named also include the Tres libri and the Libri feudorum, and at least two contain the Extravagants with Bartolus’ apparatus (Baptista de Tortis: Venezia 1489 and 1500). The same Baptista de Tortis published the entire Corpus with the Accursian gloss between the years 1487 and 1489 (repr. Torino 1968–1969 as vols. 7–11 in the reprint series Corpus glossatorum iuris civilis). De Tortis also published the Institutes in 1489, but as a separate volume. Later they were included in the 5th vol. of the Corpus, the whole being called ‘Volumen parvum’. We analyze de Tortis editions below. The originals are now all available online, with the exception of the Codex, which is available online in a de Tortis print of the following year. While the humanists focused on getting the base text of the Corpus right, they continued to publish the text with the Accursian gloss, adding notes of their own in the outer margin. They were not as careful with the text of the gloss as they were with the base text. The text of the gloss remained largely as it was in the incunabula. Probably the best known of the humanist editions is that of Denis de Godefroy, first published in Geneva in 1588. The edition continued to be reprinted into the 18th century, but the Accursian gloss dropped out in the early years of the 17th century. We analyze here the edition published by Horace Cardon in Lyon in 1604 in 6 vols.: ‘Corporis Justinianaei [Digestum vetus, etc.] commentariis Accursii, scholiis Contii, paratitlis Cuiacii et quorumdam aliorum Doctorum virorum observantibus novae accesserunt ad ipsum Accursium Dionysii Gothofredi, I. C. Notae, in quibus Glossae obscuriores explictae sunt: similes & contrariae adiectae: vitiosae in dictione, historia, vel iure notatae: verae defensae’. We have also analyzed online the quite remarkable contents of the 6th volume with links to the volume itself. Much of what the humanists thought about the Accursian gloss can be learned here. The hyperlinks in the analysis below bring you to a similar list of contents (title by title) with a link to the text itself. |

| No. 01 |

Apparatus ad Digesum vetus. |

| Early Printed Editions |

Digestum vetus. Venezia: Baptista de Tortis, 4.viii.1488 (GW 7667) (online). |

|

[Corpus iuris civilis,] vol. 1, Godefroy ed.: Digestum vetus. Lyon: Horace Cardon, 1604 (online). |

| No. 02 |

Apparatus ad Infortiatum. |

| Early Printed Editions |

Infortiatum. Venezia: Baptista de Tortis, 8.iv.1488 (GW 7687) (online). |

|

[Corpus iuris civilis,] vol. 2, Godefroy ed.: Infortiatum. Lyon: Horace Cardon, 1604 (online). |

| No. 03 |

Apparatus ad Digesum novum. |

| Early Printed Editions |

Digestum novum. Venezia: Baptista de Tortis, 9.i.1487/88 (GW 7711) (online). |

|

[Corpus iuris civilis,] vol. 3, Godefroy ed.: Digestum novum. Lyon: Horace Cardon, 1604 (online). |

| No. 04 |

Apparatus ad Codicem. |

| Early Printed Editions |

Codex. Venezia: Baptista de Tortis, 8.xii.1488 (GW 7736) (online). The online edition is that of 22.iii.1490 (GW 7739) and includes the summaries of Hieronymus Clarius. |

|

[Corpus iuris civilis,] vol. 4, Godefroy ed.: Codex. Lyon: Horace Cardon, 1604 (online). |

| No. 05 |

Apparatus ad Institutiones. |

| Early Printed Editions |

Institutes. Venezia: Baptista de Tortis, 1489.07.01 (GW 7621) (online). |

|

[Corpus iuris civilis,] vol. 5, Godefroy ed.: Institutes. Lyon: Horace Cardon, 1604 (online). At the end of the online list. |

| No. 06 |

Apparatus ad Tres Libros. |

| Early Printed Editions |

Tres libri. Venezia: Baptista de Tortis, 1489.05.07 (GW 7762) (online). |

|

[Corpus iuris civilis,] vol. 5, Godefroy ed.: Tres libri. Lyon: Horace Cardon, 1604 (online). |

| No. 07 |

Apparatus ad Authentica. |

| Early Printed Editions |

Authentica. Venezia: Baptista de Tortis, 1489.05.07 (GW 7762) (online). |

|

[Corpus iuris civilis,] vol. 5, Godefroy ed.: Authentica. Lyon: Horace Cardon, 1604 (online). |

| No. 08 |

Apparatus ad Libros feudorum. |

| Early Printed Editions |

Libri feudorum. Venezia: Baptista de Tortis, 1489.05.07 (GW 7762) (online). |

|

[Corpus iuris civilis,] vol. 5, Godefroy ed.: Libri feudorum. Lyon: Horace Cardon, 1604 (online). |

Text(s) – Modern Editions |

| No. 00 |

All texts. |

| Modern Editions |

There are many transcriptions from manuscripts of Accursian glosses in the literature that has built over the years, but we list below the only attempt at a critical edition of any of A’s apparatus |

| No. 05 |

Apparatus ad Institutiones. |

| Modern Editions |

Corpus Iuris Civilis cum Glossa Magna Accursii Florentini: Institutionum Iustiniani Augusti [Liber I], ed. P. Torelli (Bologna n.d. [193– ?]). (Copies are rare. All that was published was large-folio fascicles of liber 1, with a title page and a brief editorial introduction designed for the whole work. The title page tells us that the work was published under the auspices of the Reale Accademia d’Italia. Torelli collated a very large number of manuscripts, but he was unable to create a stemma. His notion was that the apparatus went through two recensions, and that idea has largely been accepted. In the edition, however, rarely committed himself to what belonged to the first recension and what to the second. He normally just noted a large number of variants. Although Torelli lived until 1948, the project was not continued. The war and the ultimate collapse of the political regime probably had something to do with it. G. Diurni (‘Glossa’ 347–351), however, suggests, on the basis of his later published work, that Torelli became disenchanted with his results, and came to the conclusion that what really had to be done was to search for the pre-Accursian glosses that went into making up the apparatus. That search continues to this day.) |

Literature |

|

A. Stella, The Libri Feudorum (The ‘Books Of Fiefs’): An Annotated English Translation of the Vulgata Recension with Latin Text (Medieval Law and its Practice 38; Leiden 2023). |

|

H. Jakobs, ‘Irnerius’ Sigle’, ZRG Rom. Abt. (2017) 444–490. |

|

G. Morelli, ‘Accursio (Accorso)’, in DGI (2013) 1.6–9. |

|

N. Sarti, ‘Accursio’, in Contributo italiano alla storia del pensiero = Enciclopedia italiana Appendice ottava – Il diritto, P. Cappellini, P. Costa, M. Fioravanti, and J. Schröder, ed. (Roma 2012) 47 f. (online). |

|

G. Morelli, ‘Accursio’, in Autographa, I.2: Giuristi, giudici et notai (sec. XII–XVI med.), G. Murano, ed. (Centro interuniversitario per la storia delle università italiane, Studi 16; Bologna 2012) 15–21. |

|

H. Dondorp and E. Schrage, ‘The Sources of Medieval Learned Law’, in The Creation of the |

|

F. Dorn, ‘Accursius’, in Deutsche und Europäische Juristen aus neun Jahrhunderten, G. Kleinheyer and J. Schröder, ed., 3d ed. (Heidelberg 2008) 13–17. |

|

H. Jakobs, Magna Glossa, Textstufen der legistischen glossa ordinaria (Rechts- und Staatswissenschaftliche Veroffentlichungen der Görres Gesellschaft n.F. 114; Paderborn 2006). |

|

A. Fernández de Buján, ‘Acursio’, in Juristas universales (2004) 1.421–427 (online). |

|

G. Morelli, ‘Nuovi documenti per servire alla biografia di Accursio glossatore’, RSDI, 77 (2004) 17–51 (online). |

|

F. Soetermeer, ‘Doctor suus? Accursius et J. Balduin’, SG, 29 (1998) 795–814. |

|

F. Soetermeer, ‘Utrumque ius in peciis’, in Aspetti della produzione libraria a Bologna tra Due e Trecento (Milano 1997). Reprinted in: Die Produktion juristischer Bücher in italienischen und französichen Universitäten des 13.und 14. Jahrhunderts (Frankfurt a. M. 2002) (in German with changes and additions). |

|

H. Lange, Glossatoren (1997) 335–372. |

|

E. Cortese, Il rinascimento giuridico medievale, 2nd ed. (Roma 1996). |

|

G. Speciale, La memoria del diritto comune: Sulle tracce d’uso del Codex di Giustiniano (secoli XII–XV) (Roma 1994). |

|

G. Diurni, ‘La Glossa accursiana: stato della questione’, RSDI, 64 (1991) 341–362. |

|

P. Weimar, ‘Die Handschriften des Liber feudorum und seiner Glossen’, RIDC, 1 (1990) 31–98. |

|

N. Sarti, Un giurista tra Azone e Accursio. Iacopo di Balduino (. . . 1210–1235) (Milano 1990). |

|

G. Speciale, ‘Acursius fuit de Certaldo’, RIDC, 1 (1990) 111–120. |

|

F. Soetermeer, ‘Ordre chronologique des apparatus d’Accursio sur les Libri ordinarii’, in Historia del derecho privado: Trabajos en homenaje a Ferran Valls i Taberner, M. Peláez, ed. (Estudios interdisciplinares en homenaje a Ferran Valls i Taberner con ocasión del centenario de su nacimiento, 10; Barcelona 1989) 2867–2892 (online). |

|

F. Martino, ‘Una perduta summa Authenticorum di Acursio’, RSDI, 61 (1988) 171–179. |

|

V. Valentini, ‘L’ordine degli apparati accursiani in una notizia di Angelo degli Ubaldi’, TRG, 53 (1985) 99–134. |

|

P. Weimar, ‘Zur Entsehung des azoschen Digestensummen’, in Satura Roberto Feenstra: sexagesimum quintum annum aetatis complenti ab alumnis collegis amicis oblata, J. Ankum, J. Spruit, and F. Wubbe, ed. (Fribourg 1985) 371–392. |

|

M. Bellomo, ‘Consulenze professionali e dottrine di professori: Un inedito “consilium domini Accursii”’, Quaderni catanesi di studi classici e medievali, 4 (n. 7-8) (1982) 199-219. Reprinted in: idem, Inediti della giurisprudenza medievale (Frankfurt 2011) 47–62. |

|

P. Weimar, ‘Accorso, Francisco’, in LMA (1980) 1.75–76 (online). |

|

Thomas Diplovatatius, Liber de claris iurisconsultis, F. Schulz, H. Kantorowicz, and G. Rabotti, ed. (SG 10; Bologna 1968) 81–95. (Edited from a mid-16th century manuscript of a lost original of 1511.) |

|

Atti del Convegno Internazionle di Studi Accursiani, G. Rossi, ed., 3 vols. (Milano 1968). (=Studi Accursiani.) |

|

P. Colliva, ‘Documenti per la biografia di Accursio’, in Studi Accursiani (1968) 2.383–458. |

|

G. Gualandi, ‘Un gustoso episodio della vita di Accursio e la data della composizione della “glossa magna” al “Digestum vetus”’, in Studi Accursiani (1968) 2.461–492. |

|

P. Fiorelli, ‘Accorso’, in DBI (1960) 1.116–121 (online). |

|

P. Fiorelli, ‘Minima de Accursiis’, ASD, 2 (1958) 345–359. |

|

E. Genzmer, ‘Zur Lebensgeschichte des Accursius’, in Festschrift für Leopold Wenger (München 1945) 2.223–241. |

|

H. Kantorowicz, ‘The Quaestiones Disputae of the Glossators’, TRG, 16 (1939) 1–67. Reprinted in: idem, Rechtshistorische Schriften, H. Coing and G. Immel, ed. (Freiburger Rechts- und Staatswissenschaftiche Abhandlungen 30; Karlsruhe 1970) 137–185. |

|

P. Torelli, ‘Per l’edizione critica della glossa accursiana’, RSDI, 7 (1934) 429–586. |

|

H. Kantorowicz, ‘Accursio e la sua biblioteca’, RSDI, 2 (1929) 35–62, 193–212 (online). (The link is to the first part of the article only.) |

|

M. Sarti and M. Fattorini, De claris archigymnasii Bononiensis professoribus a saeculo XI usque ad saeculum XIV, 2 vols. (Bologna 1888–1896) 151–163 (online). (1st ed. Bologna 1769.) |

|

F. von Savigny, Geschichte 5.262–279. |

|

Guido Panciroli, De claris legum interpretibus (Leipzig 1721) 119–121 (online). (The first ed. was published posthumously by his nephew, Venezia 1637.) |

|

Antonio Nicelli, Concordantie glossarum iuris canonici et civilis (Lyon 1515) (online). (Also in TUI 1584 18.187ra–221rb. The title reported by Dondorp and Schrage [De concordia glossarum seu de glossis contrariis et de eorum concordantiis] is not that of the 1515 ed. or that of the TUI ed. [De concordia glossarum]. Their number of contradictions [121] corresponds to the number found in the 1515 ed. [fol. 93va], but takes no account of the facts that, on the one hand, the work includes contradictions found in canonic sources, but, on the other, the printing seems to be incomplete. E. Mongiano, in DGI s.n. Nicelli, Cristoforo. There is also an incunabulum of Milano 1499, GW M26143 [online] and an edition of Milano 1506. WorldCat. All have a title similar to ed. Lyon 1515.) |