| The Harvard Law School’s Collection of Medieval English Statute Books and Registers of Writs |

Click on image for more information |

HLS MS No. 49 |

England. Statutes. Magna Carta to 25 Edw. I |

ca. 1297 |

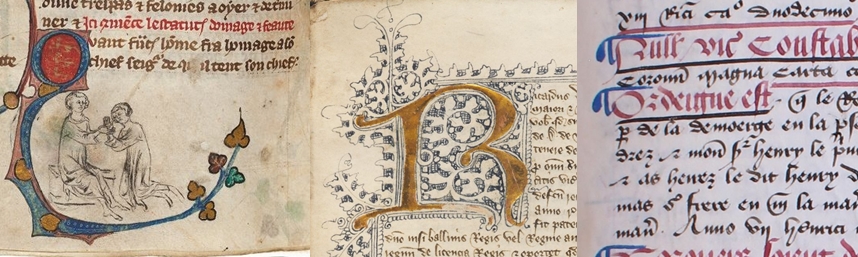

<Preliminary introduction> The HOLLIS cataloguing may be found here. The following items are worth repeating: “Description: 90 leaves : vellum ; 17 cm. “Notes: Written in neat small legal characters by an English scribe, the Calendar in red and black, containing numerous illuminated initials throughout. “Imperfect at both ends and other places.” The cataloguing in Baker’s English Legal Manuscripts, 1, no. 72 reads as follows: “REGISTRUM BREVIUM “MS. 49. “Early C.xiv, 90 ff., illum. initials. Preceded by a calendar; a table of chapters of the statutes; notes on the evangelists. The register is imperfect at both ends and in other places. It includes a writ removing the Bench to Shrewsbury because of the war in Wales. “The calendar includes obits of Robert de Orford [d. 1310], bishop of Ely; of various members of the Sewall family from 1335 to 1400; of John Totel (d. 1462) and John Totehill (d. 1507); and of Otis Abrycotehill (d. 1521); ‘C.C. Num. 32’ (on fly); belonged to Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Barrois (d. 1855) (MS. 227); sold by him to Bertram (d. 1878), 4th earl of Ashburnham; passed to his son, the 5th earl; his sale, S. 14 June 1901, no. 556 to Ellis for George Dunn; his sale, S. 11 Feb. 1913, no. 163; bought privately by HLS. “Census, 1, 1032, no. 49; Early Registers, xxvi.” As will be seen below, we are inclined to date the manuscript earlier than have previous cataloguers; the count of the medieval folios is 91 rather than 90, and Baker’s ‘Notes on the Evangelists’ turn out to be extracts from the Gospels. The manuscript is approximately 170 X 105 mm. The binding probably dates from the 19th century. It is in good condition: black morocco decorated with gold lines on both covers and gold lettering and stylized gryphon decoration on the spine. The script and decoration is discussed below with the individual items. The overall condition of the manuscript is generally quite good. There is some bleeding of the decorated capitals onto the back side of the page on which they are found. The manuscript, however, lacks a considerable amount of its original contents, as will be explained more fully below. A modern pencilled foliation is found in the lower left-hand corner. It is not always visible on the images, but where it is, it corresponds to our digital foliation, and we have used it. We did not find any earlier foliation in the manuscript until we reached the register of writs. Here there is a medieval foliation in the upper right-hand corner. We have indicated it in the detailed table of contents below. There are no signature markings, and the binding is fairly tight. Also, as the detailed contents show, there is much missing. We have been aided by the medieval foliation in the register of writs. The collation, however, must be quite speculative. A careful physical examination of the manuscript might show more. As it is, the statute-book fits quite nicely into what we have if we assume regular quaternions. The medieval foliation of the register also maps quite nicely, if we assume regular quaternions and two missing folios at the end.1 If, however, we try to reconcile this quiring with the medieval foliation on the register, the story becomes more complicated. 1. Fol. 91v is difficult to read at the bottom, but it certainly does not look as if it is the end of the writ, much less of the register. Support for the proposition that there was more may be found HLS MS 24, which is roughly contemporary. At the end of that register (fol. 60r) there is a writ that could be read to be called ‘De namiis habendis in abbathia’. The same writ appears on fol. 91r of our manuscript. At the bottom of fol. 91v in our manuscript is another writ which seems be ‘De eodem’, and is clearly that on fol. 60v of MS 24. What can be read of the writ on fol. 91v matches the same writ in MS 24. The writ in MS 24 is quite long. It certainly would have run over onto a putatative fol. 92r of our manuscript. Whether our manuscript also originally contained the rest of the writs that appear on fol. 60v of MS 24 we need not decide. Had they so appeared, considering the different size of the two manuscripts, they would almost certainly have filled, or come close to filling, two more folios. Hypothetical collation of the original manuscript (the foliation is also hypothetical for the statute-book; it tracks the existing medieval foliation for the register): 1–38 (f. 1–24), 48 (f. 25–32, now missing), 5–98 (f. 33–72), 108 (register f. 1–8, now missing), 118 (register f. 9–16), 128 (register f. 17–24, now missing), 138 (register f. 25–32, now missing, except for f. 32), 148 (register f. 33–40, f. 33–39 survive), 158 (register f. 41–48, f. 42–45 survive), 168 (register f. 49–56, now missing), 178 (register f. 57–64, f. 62–63 survive), 188 (register f. 65–72, f. 65–68, 70 survive). To map this onto the current foliation we must assume that the binder remade some of the quires. He was, we might imagine, faced with a stack of loose partial quires and single folios that would have had to be remade. What is now the second quire of the register begins one folio too soon from the point of view of the medieval foliation. (It should be register fol. 33, not 32.) That meant that the binder was faced with a loose folio from the end of what was originally quire 13 of the manuscript and a loose folio from what was originally the beginning of quire 14 (the corresponding folio at end, the orginal register fol. 40, being missing). He sewed up the package so that it seemed like a quaternion. The orginal quire 15 (register fol. 41-48) probably survived as a bifolium (register fol. 44-45) and two loose folios (register fol. 42 and 43 lacking their corresponding folios). The binder joined them with the two loose surviving folios of original quire 17, making what looks like a ternion. Register fols. 67 and 70 may have survived as a bifolium. If they did, the binder joined the loose register fols. 65 and 66 to it, and tipped in 68 between 67 and 70, producing something that looked like a duernion with one tipped in. Current quiring/collation: 14 (unfoliated), 2–98 (f. 1–64, lacks 1 quire between f. 24 and 25), 10–118 (f. 65–80, lacks 1 quire before f. 65; lacks 2 quires less one before f. 73), 126 (f. 81–86, lacks 2 folios before f. 81, 1 quire and 5 folios before f. 85, 1 folio after f. 86), 134 (f. 87–91, lacks 1 folio before f. 91, 2 after f. 91; + 1 tipped in between f. 89 and 91), 144 (unfoliated) What we have imagined above is certainly not the only mathematical possiblity. It does, however, seem the simplest explanation of the evidence as we can see it. It assumes a rather extraordinary effort on the part of a 19th-century binder, but any of the possible mathematical combinations would have required such an effort. He did a good job, and it has survived for more than a century. It is hard to know how this quite handsome medieval manuscript came lose so much of its contents. What we have is consistent with the hypothesis that at some time in the early modern period it lost whatever medieval binding it had and was subjected to some pretty rough treatment. Quires were lost; individual folios were lost. The 19th-century binding seems to have put an end to the loss, but by that time, the damage was done. The manuscript is divided into three main sections: (1) a calendar, which appears at the beginning (fol. 1–8); (2) a statute-book, which has capitularia of the longer statutes, a short section of what seem to be previously omitted statutes, and the statute-book proper, beginning with Magna Carta and ending with the View of frankpledge, temp. incert. (fol. 9–64), and (3) a register of writs (fol. 65–91). The main calendar is laid out in red, blue, and black, with the initial ‘K’ on each page decorated in gold leaf. It deserves more attention than we have been able to give it. It seems to include a number of non-standard saints (e.g., Victorinus, fol. 4r). Easter is marked for 28 March, something that did not happen between 1288 and 1349. The first folio of the quire that contains the calendar is dirty, as if it was once on the outside of a stack of unbound quires. The dorse of the first folio contains medieval notes that seem to relate to the calendar. Fol. 2r is a full page of medieval writing in an informal script that seems to contain mostly prayers. Fol. 2v may be a computus, a table for calculating Easter day, but it is not in a form with which we are familiar. January is on fol. 3r. The calendar contains a number of obits, almost certainly added later, of which the earliest is that of Robert Orford, bishop of Ely (d. 1310). The statute-book is quite straightforward. The most unusual item comes after the capitularia where the small collection of statutes that are omitted from the main collection is preceded by a short collection of readings from the Gospels for the Christmas and Easter seasons. It closes with Luke 11:27–28, which was frequently read on feasts of the Blessed Virgin, and continues on the same page with Dies communes in banco. The register of writs begins in mid-entry. The medieval foliation suggests that the first eight folios are missing. These would have contained the writ of right and its variants. The medieval foliation also skips a number of times in the course of the register, suggesting that the register itself is lacunose. The introduction to the table of writs confirms that this is the case and attempts to reconstruct what the full register might have looked like. Whether anything is missing after fol. 91 is harder to determine. If there is anything missing, it is probably not much. The last folio of the register is darkened, as if it was once the outer back folio of an unbound stack of quires. The style of the statute-book, including the additional statutes at the beginning, and the register of writs is remarkably consistent. Each item is introduced with a heading in litterae notabiliores in a script that contains relative few ligatures. The main body of text is written in a small, consistent, reasonably clear semi-cursive script, typical of English legal manuscripts of the late 13th and early 14th centuries. While the style is quite typical of English statute-books, it is much less typical of registers of writs. The program of illustration is also consistent across the two main sections of the manuscript. Main paragraphs are begun with capitals illuminated in red and blue, some with scroll work in the margins. The statute-book has red and blue alternating paragraph marks. These are lacking in the register, but most of the blocks of text in the register are quite short and lack obvious places to add a paragraph mark. We are not expert enough to say that the artist is the same throughout, but it is obvious to the non-expert that the art-work throughout is consistent in style, down to the use of the same floral design within the circles of the capitals. The latest datable item in the manuscript is Edward the First’s inspeximus of Magna Carta of 1297. There is considerable evidence that this date is close to the composition of the statute-book. The excommunication of violators of the Charter is that issued by the prelates in the time of Henry III, not that issued in connection with the confirmation of the Charter in 1297. The next most recent statute is Quia emptores (1290) with the unusual title: ‘Ne fiat medius [inter] capitalem dominum et tenentem’ (reconstructed from the explicit, fol. 62v). The latest datable item in what we have of the register of writs is even earlier, Westminster II of 1285, and this is not fully integrated into the register. There are, for example, no writs of formedon, at least in what we have. We thus have data points for the dates of each of the three items: 1288, the Easter date in the calendar, 1297 for the statute-book, and 1285 for the register of writs. The consistency in style between the statute-book and the register argues for their being composed at approximately the same time. We would not want to date either of them much later than 1297. 1297 is the date of the last datable item in the statute-book, and the register seems already to have been out of date at that point. We can be less sure about the calendar. What links it with the statute-book is that the calendar has some evidence that is was made for and used by an ecclesiastic (the prayers are in Latin and not standard) and that the owner of the statute-book wanted something specifically religious in it (the gospel extracts). We cannot be sure that the calendar was not joined with the statute-book and the register until some later date, but it seems likely that it was so joined from the beginning. Further argument supporting the dating of the register of writs is given in the introduction and conclusion to the table of writs. We recognize that we are disagreeing here with Hall, whom Baker followed. One disagrees with Hall on the dating of registers of writs at one’s peril. His date, however (14th century and not particularly early in the century), is contained in a footnote to a list of manuscripts; there is no evidence that he analyzed he contents of the register, much less of the statute-book. Neither the statute-book nor the register, particularly the latter, is in a form that would be of use to a practicing lawyer. Neither is particularly full. The register, even if we imagine what is not now there, is really quite skimpy. It is also, as we have noted, out of date if we place its composition around or just after 1297, and it contains none of the markings of notae and regulae that are characteristic of professional registers of writs. The manuscript also does not contain any of those short treatises that are found in the statute-books and registers of writs of practicing lawyers and law teachers. Indeed, the writs are treated as if they were almost on the same par, and subject to the same type of interpretation, as the statutes. For those who are willing to speculate, it is tempting to combine these scraps of evidence and suggest that the book originally had an ecclesiastical owner. The fact that it seems to have fallen into lay hands later in the 14th century suggests, though it certainly does not prove, that it was the property of a prelate rather than of a religious house. Robert Orford, the first name mentioned in the calendar, is an unlikely original owner. See Owen, in ODNB, s.n. But his predecessor and patron Ralph Walpole, bishop of Norwich and ultimately of Ely, is a possibility. He was a theologian, but became involved in secular politics during the controversy over royal taxation of the church, beginning, interestingly enough, in 1297. See Owen, in ODNB, s.n. That the book later fell into the hands of a family named Sewall (Sewell), a Norfolk name, is consistent with this speculation. |

Summary Contents |

| Clicking on the item in question will open the first sequence for the item in the PDS in a new tab or window. |

Detailed Contents |

| Clicking on the sequence number will open that sequence in the PDS in a new tab or window. |

| Seq. | Fol. | Label | Header | MsFol. | |

| 1 | no fol., no sig. | Spine | |||

| 2 | no fol., no sig. | Front cover | |||

| 3 | no fol., no sig. | Inside back cover, with bookplate, From the Library of George Dunn of Woodley Hall Near Maidenhead; entry from auction catalogue pasted in | |||

| Note: The entry is from The Ashburnham library: Catalogue of the portion of the famous collection of manuscripts, the property of the Rt. Hon. the Earl of Ashburnham, known as the Barrois collection (London 1901) no. 556, p. 203. | |||||

| 4 | no fol., no sig. | Library reference mark and notes of acquisition in George Dunn’s hand | |||

| 5 | no fol., no sig. | Blank | |||

| 6 | no fol., no sig. | Blank | |||

| 7 | no fol., no sig. | Blank | |||

| 8 | 1r | Notes | |||

| Note: In early modern hand ‘C. C. Num. 32’; various faded notes in medieval hands that could possibly be read under uv. | |||||

| 9 | 1v | Notes | |||

| Note: In a medieval hand, probably concerning the calendar that follows. | |||||

| 10 | 2r | Notes | |||

| Note: A full page of medieval text, which seems to be mostly prayers. | |||||

| 11 | 2v | Calendar | |||

| 12 | 3r | ||||

| Note: (1) All pages of the main calendar are laid out in red, blue, and black, with the initial ‘K’ on each page decorated in gold leaf. (2) This page contains in the margin the obit of Robert de Orford, bishop of Ely (d. 1310). The date is identified in pencil in George Dunn’s hand, and is almost certainly the source of his date for the manuscript on seq. 4: ‘probably before Jan. 1310’. | |||||

| 13 | 3v | ||||

| 14 | 4r | ||||

| Note: Easter is marked for 6 Kal. April (i.e., 28 March). | |||||

| 15 | 4v | ||||

| 16 | 5r | ||||

| 17 | 5v | ||||

| 18 | 6r | ||||

| 19 | 6v | ||||

| 20 | 7r | ||||

| Note: Obits of various members of the Sewall family from 1335 to 1400. | |||||

| 21 | 7v | ||||

| 22 | 8r | ||||

| 23 | 8v | ||||

| 24 | 9r | Capitularia of statutes | |||

| Heading: Hic incipiunt capitula magne carte de libertatibus Anglie R. | |||||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘H’. | |||||

| 25 | 9v | ||||

| Heading: (1) Expliciunt capitula magne carte Incipiunt capitula carte de foresta. (2) Expliciunt capitula carte de foreste Incipiunt capitula de mertona. | |||||

| 26 | 10r | ||||

| Heading: Expliciunt capitula de merton’ Incipiunt capitula de marlebg’. | |||||

| 27 | 10v | ||||

| Heading: Expliciunt capitula de marleberg’ Incipiunt capitula Westm’ primi. | |||||

| 28 | 11r | ||||

| Heading: Expliciunt capitula Westm’ primi. | |||||

| 29 | 11v | ||||

| Heading: (1) Incipiunt capitula de Gloucestr’. (2) Expliciunt capitula statuti Gloucestr’ Incipiunt capitula statuti Westm’ secundi. | |||||

| 30 | 12r | ||||

| 31 | 12v | ||||

| Heading: Expliciunt statuta Westm’ secundi. | |||||

| 32 | 13r | Blank except for pencilled layout | |||

| 33 | 13v | Gospel readings for Christmas and Easter seasons, etc. | |||

| Heading: (1) Sc’dm luca’. (2) Sc’dm matheum. | |||||

| Note: (1) Luke 1:26-38. (2) Matthew 2:1-12Elaborately decorated initials ‘M’ and ‘C’. | |||||

| 34 | 14r | ||||

| Heading: Scd’ marcum. | |||||

| Note: (1) Elaborately decorated initial ‘R’. (2) Mark 16:14–20. | |||||

| 35 | 14v | ||||

| Heading: Inicium sci’ evangelii scd’ joh’em. | |||||

| Note: (1) Elaborately decorated initial ‘I’. (2) John 1:1–14. | |||||

| 36 | 15r | Dies communes in banco, temp. incert. (S.R. 1:208) | |||

| Heading: (1) Scd’m lucam. (2) Incipiunt dies communes in Banco. | |||||

| Note: (1) Decorated initials ‘I’ and ‘S’. (2) Luke 11:27–28. | |||||

| 37 | 15v | (1) Circumspecte agatis (pt. 2), 13 Edw. 1. (2) Statute of gavelet in London, temp. incert. (S.R. [1] 1:101–2 [2] 1:222) | |||

| Heading: (1) Expliciunt dies communes in banco Inc’ stat’ layti impetrat’ regalem prohibo’z. (2) Explic’ stat’ qualit’ layci’ ip’ reg’ p’hib Inc’ stat’ de gavelet. | |||||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘S’ and ‘P’. | |||||

| 38 | 16r | Modus calumpniandi essoniam, temp. incert. (S.R. 1:217–18) | |||

| Heading: Explic’ statutut’ de Gavelet Inc’ modus calumpniandi Esson’. | |||||

| 39 | 16v | ||||

| Heading: Explic’ modus calumpniendi Essoniar’. | |||||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘H’. | |||||

| 40 | 17r | Magna Carta, as confirmed 25 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:114–19) | |||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘C’ with partial border around text. | |||||

| 41 | 17v | magna carta | |||

| 42 | 18r | magna carta | |||

| 43 | 18v | magna carta | |||

| 44 | 19r | magna carta | |||

| 45 | 19v | magna carta | |||

| 46 | 20r | magna carta | |||

| 47 | 20v | Forest Charter, as confirmed 25 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:120–2) | magna carta | ||

| Heading: Explicit magna carta Incipit carta de foresta. | |||||

| 48 | 21r | Carta de foresta | |||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘E’. | |||||

| 49 | 21v | Carta de foresta | |||

| 50 | 22r | Carta de foresta | |||

| 51 | 22v | Sentencia exommunicationis lata in transgressores cartarum, 37 Hen. 3. (S.R. 1:6–7) | Carta de foresta | ||

| Heading: Explicit carta de libertatibus forest’ Incip sentencia lata ab Archiepis Ep’is super oni’s qui cont’ easd’ ?? contrarie. | |||||

| 52 | 23r | Sentencia data | |||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘A’. | |||||

| 53 | 23v | Provisions of Merton, 20 Hen. 3. (S.R. 1:1–4) | sn’ia rata. Mertone | ||

| Heading: Explicit sentencia data super omnes qui con’ easdem ?? contrarie Incipiunt provisiones de mertona. | |||||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘P’. | |||||

| 54 | 24r | merton’ | |||

| 55 | 24v | mertone | |||

| Note: The page ends in the middle of the Provisions of Merton. One quire is probably missing, which would have contained the end of the Provisions of Merton, the Statute of Marlborough (included in the capitularia), and the beginning of the Statute of Gloucester. | |||||

| 56 | 25r | Statute of Gloucester, 6 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:47–50) | Gloucestr’ | ||

| Note: The page begins in the middle of the Statute of Gloucester. | |||||

| 57 | 25v | ‘Explanation’ of statute of Gloucester, 6 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:50) | Gloucestr’. Explanaco’es eor’dem | ||

| Heading: Explic’ stat’ Glouc’ Inicipiunt explanaciones eorumdem. | |||||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘P’. | |||||

| 58 | 26r | Statute of Exeter, temp. incert. (S.R. 1:210–12) | Explanaco’es. statuta exon’ | ||

| Heading: Expliciunt explanaciones Incipiunt statuta Oxon’. | |||||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘P’. | |||||

| 59 | 26v | Oxon’ | |||

| 60 | 27r | Statutum de iusticiis assignandis, quod vocatur Rageman, 4 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:44) | Oxon’ | ||

| Heading: Explic’ statut’ oxon’ Incip’ Rageman. | |||||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘P’. | |||||

| 61 | 27v | Statute of Westminster I, 3 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:26–39) | Rageman. Westm’ p’im’ | ||

| Heading: Explic’ stat’ de Ragema’ Inc’ Westm’ p’mi. | |||||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘C’. | |||||

| 62 | 28r | Westm’ primi | |||

| 63 | 28v | Westm’ primi | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘E’. | |||||

| 64 | 29r | Westm’ primi | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘D’. | |||||

| 65 | 29v | Westm’ p’mi | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘E’, ‘E’, and ‘S’. | |||||

| 66 | 30r | Westm’ p’mi | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘P’, and ‘P’. | |||||

| 67 | 30v | Westm’ p’mi | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘P’ and ‘P’. | |||||

| 68 | 31r | Westm’ primi | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘C’ and ‘P’. | |||||

| 69 | 31v | Westm’ p’mi | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘P’. | |||||

| 70 | 32r | Westm’ p’mi | |||

| 71 | 32v | Westm’ p’mi | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘P’, ‘P’, ‘E’, and ‘D’. | |||||

| 72 | 33r | Westm’ p’mi | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘P’ and ‘N’. | |||||

| 73 | 33v | Westm’ p’mi | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘E’, ‘P’, and ‘E’. | |||||

| 74 | 34r | Westm’ p’mi | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘D’, ‘D’, ‘D’ and ‘D’. | |||||

| 75 | 34v | Westm’ p’mi | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘P, ‘P’, ‘D’, and ‘P’. | |||||

| 76 | 35r | Westm’ primi | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘P’ and ‘P’. | |||||

| 77 | 35v | Westm’ primi | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘P’, ‘P’, ‘P’, and ‘D’. | |||||

| 78 | 36r | Westm’ p’mi | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘P’ and ‘P’. | |||||

| 79 | 36v | Statute of Westminster II, 13 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:71–95) | Westm’ primi | ||

| Heading: Expliciunt statuta Westm’ primi Incipiunt statuta Westm’ secundi. | |||||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘P’. | |||||

| 80 | 37r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘C’. | |||||

| 81 | 37v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘Q’. | |||||

| 82 | 38r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘E’ and ‘E’. | |||||

| 83 | 38v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘I’. | |||||

| 84 | 39r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘I’. | |||||

| 85 | 39v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘C’. | |||||

| 86 | 40r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘E’ and ‘C’. | |||||

| 87 | 40v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘D’, ‘E’, and ‘E’. | |||||

| 88 | 41r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘E’, ‘E’, and ‘E’. | |||||

| 89 | 41v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘C’, ‘C’, and ‘C’. | |||||

| 90 | 42r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘C’. | |||||

| 91 | 42v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| 92 | 43r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘C’. | |||||

| 93 | 43v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘C’ and ‘D’. | |||||

| 94 | 44r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘Q’ and ‘Q’. | |||||

| 95 | 44v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘C’, ‘I’, ‘I’, and ‘I’. | |||||

| 96 | 45r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘C’, ‘C’, ‘C’, ‘C’, and ‘C’. | |||||

| 97 | 45v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘I’ and ‘Q’. | |||||

| 98 | 46r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘E’. | |||||

| 99 | 46v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘D’. | |||||

| 100 | 47r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘P’, ‘B’, and ‘A’. | |||||

| 101 | 47v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘I’ and ‘C’. | |||||

| 102 | 48r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘C’ and ‘Q’. | |||||

| 103 | 48v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘P’, ‘D’, ‘Q’ and ‘D’. | |||||

| 104 | 49r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| 105 | 49v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘Q’, ‘Q’, and ‘Q’. | |||||

| 106 | 50r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘Q’. | |||||

| 107 | 50v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘M’ and ‘M’. | |||||

| 108 | 51r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘M’, ‘C’, and ‘S’. | |||||

| 109 | 51v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘D’. | |||||

| 110 | 52r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘C’, ‘P’, and ‘P’. | |||||

| 111 | 52v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initials ‘D’ and ‘D’. | |||||

| 112 | 53r | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘C’. | |||||

| 113 | 53v | Westm’ sc’di | |||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘P’. | |||||

| 114 | 54r | Statute of Winchester, 13 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:96–8) | Westm’ sc’di | ||

| Heading: Explic’ statut’ Westm’ sc’di Inc’ Wynton’. | |||||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘D’. | |||||

| 115 | 54v | Wynton’ | |||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘P’. | |||||

| 116 | 55r | Wynt’ | |||

| 117 | 55v | Wynt’ | |||

| 118 | 56r | Statute of waste, 20 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:109–10) | Wynt’ | ||

| Heading: Explic’ statut’ Wynt’ Inc’ Will’s Boteler. | |||||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘D’. | |||||

| 119 | 56v | Statutum de pistoribus, temp. incert. (S.R. 1:202–4) | Boteler | ||

| Heading: Explic’ statut’ Boteler Inc’ luc’m pistoris. | |||||

| Note: Decorated initial ‘F’. | |||||

| 120 | 57r | (1) Statute of weights and measures, temp. incert. (2) Statute of merchants (Acton Burnell), 11 Edw. 1. (S.R. [1] 1:204 [2] 1:53–4) | |||

| Heading: (1) Explicit lucrum pistor’ Inci’ compoc’ mensuraru’. (2) Explic’ statut’ compoc’ mensurarum Incip’ statut’ de Aketon’ Burnel & de mercator’. | |||||

| Note: (1) Elaborately decorated ‘P’ and ‘P’. (2) Only the first paragraph of the Statute of weights and measures. | |||||

| 121 | 57v | mercator’ | |||

| 122 | 58r | ‘Statutes of the Exchequer’, temp. incert. (S.R. 1:197 [semel] – [ter]) | mercator’ | ||

| Heading: Explic’ statut’ de mercator’ Inc’ stat’ scaccar’. | |||||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘L’. | |||||

| 123 | 58v | Statuta de sc’cario | |||

| 124 | 59r | Statuta de sc’cario | |||

| 125 | 59v | Districtiones scaccarii, temp. incert. (S.R. 1:197 [ter] – 198) | Statut’ de sc’cario. Districc’o’es eord’ | ||

| Heading: Explic’ stat’ de scaccario Incipiunt districciones eiusdem. | |||||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘P’. | |||||

| 126 | 60r | districc’o’es scaccar’ | |||

| 127 | 60v | districc’o’es scaccar’ | |||

| 128 | 61r | Statute De viris religiosis, 7 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:51) | Distr’ sc’car’ -- Statut’ Regilios’ | ||

| Heading: Explic’ distr’ sc’carii Incip’ stat’ con’ Religios’. | |||||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘C’. | |||||

| 129 | 61v | Statutum de quo warranto, 18 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:107) | Statut’ Religios’ | ||

| Heading: Explic’ stat’ de Relig’ Inc’ stat’ de quo waranto. | |||||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘Q’. | |||||

| 130 | 62r | Statute of Westminster III, 18 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:106) | de quo Waranto | ||

| Heading: Explic’ statut’ de quo War’o Inc’ ne fiat medi’. | |||||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘Q’. | |||||

| 131 | 62v | Statutum de anno et die, 40 Hen. 3. (S.R. 1:7) | Ne fiat medi’ | ||

| Heading: Explic’ statut’ ne fiat medius & ?? & ten’ Inc’ Bre’ de anno & die. | |||||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘E’. | |||||

| 132 | 63r | (1) Statute of conspirators, temp. incert; (2) Statutum de illis qui debent poni in iuratis et assisis (statute), 21 Edw. 1. (S.R. [1] 1:216 [2] 1:111) | |||

| Heading: (1) Explic’ de anno & die Incipit statut’ fact’ apud Berewyk de champertours. (2) Explic’ statut des champertours Incip’ statut’ [sic]. | |||||

| Note: The version of the second statute given here includes all of the statutory text in S.R. without the following memoranda. | |||||

| 133 | 63v | Statutum de illis qui debent poni in iuratis et assisis (writ), 21 Edw. 1. (S.R. 1:113) | |||

| Heading: Explicit statut’ Incipit breve. | |||||

| Note: (1) Elaborately decorated initial ‘E’. (2) The version of the statute given here is in the forrm of a writ to the sheriff of Nottingham and does not include all of the text that is in S.R. | |||||

| 134 | 64r | View of frankpledge, temp. incert. (S.R. 1:246–7) | |||

| Heading: Expliciunt statuta de jur’ ass’ et recogn’ Incip’ statut’ de visus francii plegii. | |||||

| Note: Elaborately decorated initial ‘C’. | |||||

| 135 | 64v | ||||

| Heading: Explic’ statut’ de visu francii plegii. | |||||

| Note: [One?] fol. missing. | |||||

| 136 | 65r | Register of writs: Writs of right (incomplete) | Cancellar’ | 9 | |

| Heading: De duobus atturnatis amovendis et aliis duobus substituendis. | |||||

| Note: (1) Decorated initials ‘R’, ‘R’, ‘R’, and ‘R’. (2) The register begins in mid-entry. There is a medieval foliation that suggests that 8 folios are missing at the beginning of the register. Skips in the medieval foliation lead to our suggestions in the notes below as to how much may be missing. The indications of the writs are put in the center as if they were headings. These writ names are reproduced below in the separate table of writs. | |||||

| 137 | 65v | Registrum | |||

| 138 | 66r | Cancellarii | 10 | ||

| 139 | 66v | Registrum | |||

| 140 | 67r | Cancellarii | 11 | ||

| 141 | 67v | Registrum | |||

| 142 | 68r | Cancellarii | 12 | ||

| 143 | 68v | Ecclesiastical writs | Registrum | ||

| 144 | 69r | Cancellarii | 13 | ||

| 145 | 69v | Registrum | |||

| 146 | 70r | Cancellarii | 14 | ||

| 147 | 70v | Registrum | |||

| 148 | 71r | Cancellarii | 15 | ||

| 149 | 71v | Registrum | |||

| 150 | 72r | Cancellarii | 16 | ||

| 151 | 72v | Registrum | |||

| 152 | 73r | Nuisance, pasture, mesne | Cancellarii | 32 | |

| Note: ?Two quires missing before this folio. | |||||

| 153 | 73v | Registrum | |||

| 154 | 74r | Cancellarii | 33 | ||

| 155 | 74v | Registrum | |||

| 156 | 75r | Cancellarii | 34 | ||

| 157 | 75v | Debt | Registrum | ||

| 158 | 76r | Cancellarii | 35 | ||

| 159 | 76v | Registrum | |||

| 160 | 77r | Cancellarii | 36 | ||

| 161 | 77v | Registrum | |||

| 162 | 78r | Cancellarii | 37 | ||

| 163 | 78v | Warranty, customs and services, guardianship | Registrum | ||

| 164 | 79r | Cancellarii | 38 | ||

| 165 | 79v | Registrum | |||

| 166 | 80r | Cancellarii | 39 | ||

| 167 | 80v | Registrum | |||

| 168 | 81r | Cancellarii | 42 | ||

| Note: ?Two folios missing before this one. | |||||

| 169 | 81v | Registrum | |||

| 170 | 82r | Novel disseisin, nuisance | Cancellarii | 43 | |

| 171 | 82v | Registrum | |||

| 172 | 83r | Cancellarii | 44 | ||

| 173 | 83v | Registrum | |||

| 174 | 84r | Cancellarii | 45 | ||

| 175 | 84v | Registrum | |||

| 176 | 85r | Entry | Cancellarii | 62 | |

| Note: ?Two quires missing before this folio. | |||||

| 177 | 85v | Registrum | |||

| 178 | 86r | Cancellarii | 63 | ||

| 179 | 86v | Registrum | |||

| 180 | 87r | Cancellarii | 65 | ||

| Note: ?One folio missing before this one. | |||||

| 181 | 87v | Registrum | |||

| 182 | 88r | De ponendo in assisis | Cancellarii | 66 | |

| 183 | 88v | Registrum | |||

| 184 | 89r | Cancellarii | 67 | ||

| 185 | 89v | Miscellaneous (a number concerning the writ of right) | Registrum | ||

| 186 | 90r | Cancellarii | 68 | ||

| 187 | 90v | Registrum | |||

| 188 | 91r | Cancellarii | 70 | ||

| 189 | 91v | Registrum | |||

| Note: ?One folio missing before this one. One or more folios probably missing after this one.. | |||||

| 190 | no fol., no sig. | Bookplate, From the Library of George Dunn, Gift of the Alumni of the Harvard Law School | |||

| 191 | no fol., no sig. | Blank | |||

| 192 | no fol., no sig. | Blank | |||

| 193 | no fol., no sig. | Blank | |||

| 194 | no fol., no sig. | Inside back cover | |||

| 195 | no fol., no sig. | Back cover | |||

Preliminary Analysis of the Register of Writs

|

Registrum cancellarii As indicated in the Detailed Contents, the medieval foliation of the register suggests that there is a considerable amount missing. Something is clearly missing at the beginning, because the first folio, which is numbered ‘ix’, begins in mid-entry. Hence, we lack the usual writ of right patent and its variants, which are frequently quite extensive. The register begins with making attorney, a topic that frequently follows the variants on the writ of right. Whether there is something missing after the last folio (91) is less clear. Fol. 91v is darkened as if it at one time formed the end of a unbound quire. It probably is not complete at the end, but the writing is faded and hard to read. All of the skips in foliation in mid-text seem to indicate that text is missing. Either the preceding folio does not carryover as expected or the folio following the skip begins in mid-entry, or both. Since so much is missing from the register, any attempt to date it is better left until after we have examined its contents. There are no marginal notes naming the writs, nor, so far as we have yet found, any regulae or notae, so marked (though there are some pieces of text that are clearly not just part of the text of the writ). The following table gives the names of the writs as found in the headings and counts them. Two counts are given in the right-hand columns of the table. The first counts all the writs. The second excludes from the total all the writs where the heading includes the words ‘eodem’ or ‘aliter’. |

| Seq. | Fol. | Header | Writ(s) | Count | Uniq |

| 136 | 65r | Cancellarii | De duobus atturnatis amovendis et aliis duobus substituendis; De execucione iudicii nuper redditi (3 writs). | 2 | 2 |

| 137 | 65v | Registrum | De eodem sicut plures precepimus; De warentia diei quod non fuit in servicio. | 2 | 1 |

| 138 | 66r | Cancellarii | De eodem si plures fuerint loquele; De eodem si diverse fuerit dies et loquele diverse; De warantia communis summonicionis. | 3 | 1 |

| 139 | 66v | Registrum | De falso iudicio in Curia de ?N [possibly a design to fill out the line]; De eodem in dominicis domini Regis. | 2 | 1 |

| 140 | 67r | Cancellarii | Quando aliquis dicit se non debere placitare nisi coram rege vel capitali Iusticiario; De eodem vicecomiti. | 2 | 1 |

| 141 | 67v | Registrum | Attachiamenta de eodem hoc modo; De falso iudicio in comitatu. | 2 | 1 |

| 142 | 68r | Cancellarii | Pone ad peticionem petentis coi’ [?comitatu; perhaps just design to fill out the line]; Pone a parte defendentis inferius; De terra replegianda. | 4 | 4 |

| 143 | 68v | Registrum | Breve de advocacione Ecclesie; De eodem ad Bancum; Pone de eodem a parte petentis. | 3 | 1 |

| 144 | 69r | Cancellarii | Pone de eodem a parte defendentis; De atturnato de eodem faciendis; De advocacione ecclesie replegiar’; Aliter de eodem; Quare impedit. | 5 | 2 |

| 145 | 69v | Registrum | De attornato in le quare impedit; Prohibicio ne admittat personam; Quare incumbravit; De villat’ movend’. | 4 | 4 |

| 146 | 70r | Cancellarii | de eodem aliter; De vi laica amota per vicecomitem sine precepto Regis; Aliter Quare incumbravit etc’. | 3 | 1 |

| 147 | 70v | Registrum | De ultima presentacione ad Bancum; de eodem clausum; De eodem patens. | 3 | 1 |

| 148 | 71r | Cancellarii | De ultima presentacione pro Rege; De attornato in eodem; Placita de Banco ?cessant clausum; Patens. | 4 | 3 |

| 149 | 71v | Registrum | Quare non commisit etc’; De utrum clausum etc’; Patens. | 3 | 3 |

| 150 | 72r | Cancellarii | De atturnatis de eodem faciendis; Prohibicio de advocacione ecclesie; Parti de eodem; Attachiamentum de eodem per pone etc’. | 4 | 1 |

| 151 | 72v | Registrum | indicavit; Parti de eodem; indicavit pro Rege. | 3 | 2 |

| 152 | 73r | Cancellarii | De mercatis levatis ad nocumentum; De domo levata ad nocumentum; De eodem si transferatur domus vel murus; Quando pater levavit domum. | 4 | 3 |

| 153 | 73v | Registrum | De recto pasturam habere; De communa pasture de morte antecessoris; De communa pastura de disseisina; Aliter breve de eodem de communa pasture. | 4 | 2 |

| 154 | 74r | Cancellarii | De pastura ad certum numerum averiorum; De eodem in comitatu et cetera; de pastura habenda in causa alterius; De amensuracione pasture et cetera. | 4 | 3 |

| 155 | 74v | Registrum | Quo iure de communa pasture; De racionabilibus divisis faciendis; De perambulacione inter diversas. | 3 | 3 |

| 156 | 75r | Cancellarii | Breve de medio quia cetera; De medio ad bancum; Pone de medio ad peticionem petentis; De anno redditu in comitatu. | 4 | 4 |

| 157 | 75v | Registrum | Ad bancum de eodem; Pone de anno redditu; De debittis in comitatu; De eodem ad bancum. | 4 | 2 |

| 158 | 76r | Cancellarii | De eodem in quadam communitate; De eodem pro executoribus; Pone de debitis ad peticionem; de catallis reddendis in comitatu. | 4 | 2 |

| 159 | 76v | Registrum | Q’ vicecomes fit in auxilium ad debitum recuperandum; Si recognoscat se debere; De anno redditu de pecunia in banco pro quart’ frumenti. | 3 | 3 |

| 160 | 77r | Cancellarii | De atturnato in brevi de medio; De eodem de anno; De atturnato in brevi de debito; atturnato de catallis et cetera. | 4 | 3 |

| 161 | 77v | Registrum | De plegiagio acquietato in comitatu; De eodem ad bancum; Ne plegii distringantur quamdiu principalis debitor habet unde; De pecunia et catallis redditis vel p’cio eorundem. | 4 | 3 |

| 162 | 78r | Cancellarii | De eodem in comitatu; Indempnitati: pro debitis et placitis serviencium Regis; De cartis redditis in comitatu; De eodem ad bancum. | 4 | 2 |

| 163 | 78v | Registrum | Pone ad peticionem petentis de eodem; De warantizacione carte; De atturnato faciendo de eodem; De pace post breve de warantia impetratum. | 4 | 2 |

| 164 | 79r | Cancellarii | De warantia pro Religiosis non obstante statuto edito de terris non ponendis in manum mortuam; De warantia vocat’ Com’ Londonie. | 2 | 2 |

| 166 | 80r | Cancellarii | De ?communes [recte consuetudinibus] et serviciis coram Iusticiariis; De consuetudinibus in Comitatu; De eodem in burgagio. | 3 | 2 |

| 167 | 80v | Registrum | De libero passagio ultra aquam; De convencione in comitatu; De eodem ad bancum; De atturnato faciendo de eodem. | 4 | 2 |

| 168 | 81r | Cancellarii | Summonicio de eieccione custodie; Aliter de eodem pone de catallis asportatis; De eodem de hered’ maritat’. | 3 | 1 |

| 169 | 81v | Registrum | De herede rapto iuxta statutum; aliter de eodem si transferatur de uno comitatu in alium. | 2 | 1 |

| 170 | 82r | Cancellarii | De assis nove disseisine de tenementis coram iusticiariis assignantis; Patens in nove disseisina. | 2 | 2 |

| 171 | 82v | Registrum | De assisa nove disseisine de communa pasture breve clausum coram iusticiariis assignatis; Patens inde ad Iusticiarios; De assisa de libero tenemento quando vir et mulier sunt coniunctim disseisiti. | 3 | 3 |

| 172 | 83r | Cancellarii | Si mulier sit disseisita antequam habeat virum; De nova disseisina ad primam assisam. | 2 | 2 |

| 173 | 83v | Registrum | Patens de assisis ad Iusticiarios. | 1 | 1 |

| 174 | 84r | Cancellarii | De fossato iniuste levato vel prostrato; De eodem coram Iusticiariis assignatis; Patens de eodem ad iusticiarios. | 3 | 1 |

| 175 | 84v | Registrum | De stagno levato ad nocumentum; Patens inde ad iusticiarios; De sepe levato ad nocumentum; Patens inde ad iusticiarios. | 4 | 4 |

| 176 | 85r | Cancellarii | De eodem post dimissionem; De ingressu contradicere non potuit; Aliter de eodem ad vicecomitem. | 3 | 1 |

| 177 | 85v | Registrum | Aliter ?cum ?vel sint feoffati; Aliter breve post dimissionem; Pro herede de dote alienata per mulierem que tenuit in dotem. | 3 | 1 |

| Note: The first item is corrupt. The ‘cum’ has a macron over the ‘u’, and if ‘cum’ is really meant, something is missing before what seems to be ‘vel’. The following text is various forms of cui in vita. | |||||

| 178 | 86r | Cancellarii | De inquisicione post mortem mulieris que tenuit in dotem. | 1 | 1 |

| 179 | 86v | Registrum | Aliter post dimissionem; De ingressu causa matrimonii prelocuta. | 2 | 1 |

| 180 | 87r | Cancellarii | De ingressu de tenemento unde servicium redd’ si cessaverit per biennium iuxta formam statuti; De ingressu de tenemento per villanum. | 2 | 2 |

| 181 | 87v | Registrum | De ingressu post utlagariam revocatam et adiudicatam; Breve de eodem ad vicecomitem; De seisina habenda post annum et diem. | 3 | 2 |

| 182 | 88r | Cancellarii | Quod mulier hospitatur in villa de qua fuit exulata et eiecta; Quod homines etatem lxx annorum excedentes non ponantur in assisis; Attachiamentum de eodem super vicecomitem. | 3 | 2 |

| 183 | 88v | Registrum | Quando homines xl solidatas terre vel redditus non habentes non ponantur in assisis; De eodem aliter ad vicecomitem. | 2 | 1 |

| 184 | 89r | Cancellarii | Quod homines tempore sum’ vic’ non ponantur in assisis; Quod homines languidi non ponantur in assisis; Quod aliquis non vexatur in assisa quia inpotens sui. | 3 | 3 |

| 185 | 89v | Registrum | Breve patens ne aliquis ponatur in ass’; Quia homines de antiquo corone Anglie non ponantur in assisis er’ tenuram eiusdem dominici; Quod capitalis dominus possit habere Curiam suam de ten’ suo placitato per brevem de recto. | 3 | 3 |

| 186 | 90r | Cancellarii | Quod precipe in capite non fiat alium [recte alicui] de libero tenemento unde liber homo perdat curiam suam. | 1 | 1 |

| 187 | 90v | Registrum | Quando aliquis impetravit breve de pace in brevi de recto; Pro illis de Wallia. | 2 | 2 |

| 188 | 91r | Cancellarii | De banco removendo; De namiis habendis in abbath’ per Regem. | 2 | 2 |

| 189 | 91v | Registrum | Aliter de eodem ad abbat’ et convent’. | 1 | 0 |

| Note: Page darkened and text faint. | |||||

| Total: | 155 | 104 | |||

|

As we have already noted, a considerably amount is missing from this register. The initial quire is missing. There are most or all of four more quires missing in the middle of the text and four individual folios. There may be material missing at the end. If anything is missing there, it is probably not much; we have already reached the ‘miscellaneous’ section of the register. (See the Introduction.) What we have is not a large register: 155 in the longer count, 104 in the shorter. On the assumptions that the missing quires contained eight folios, that there is only one missing folio at the end, and that the missing folios contained the same average number of writs as the ones that we do have, the original register would have contained 366 (237) writs. This approximates the totals in MS 33 and 39, which are probably earlier but not much earlier. It is slightly more than half of what is contained in MS 24 and 52, which probably date from about a decade later. Lacking the initial writ of right patent, we have no firm evidence of a date for this register, but what we have suggests a date fairly early in the reign of Edward I. There are three references to statutes, two firm: Gloucester c. 4 (1278, fol. 87r), Mortmain (1279, fol. 79r), and one probable: Westminster II, c. 35 (1285, fol. 81v). The writ De banco amovendo on fol. 91r probably refers to Edward the First’s removal of the courts to Shrewsbury in 1277 at the beginning of the Welsh wars. The fact that this writ is included in the ‘miscellaneous’ section at the end suggests that that was a relatively recent event. The fact that it is included at all also suggests that it was a relatively recent event. The further away that we get from the end of the Welsh wars in 1283, the less likely it would be that this writ would be of interest. What we have contains nothing about trespass or crime. The personal actions are, basically, limited to debt (Covenant is very skimpy.) There is no waste, no replevin, no account, no mort d’ancestor. All of these writs could have been included on the quires or folios that are now missing. The writs of entry are confined to those in the first degree, with no per or cui, and certainly no post. There is no formedon. Before we draw the conclusion, however, that this is a register from time of Henry III, with a bit of updating, we should bear in mind that the limitation period for novel disseisin the voyage of Henry III to Gascony, reflecting the limitation period of Westminster I, c. 39, the references to Gloucester and Mortmain are specific, and that to Westminster II, c. 35, while not specific (‘iuxta statutum’), heads a trespassory writ De herede rapto, identical to that found in Hall’s R 580. At least as so far discovered, then, there is nothing that would put this register much after 1285, but it does seem to have been made after that date. By contrast with is missing, the collection of ecclesiastical writs is relatively full. There are many writs concerning the making of attorneys and a number of writs pone. Portions of the groups of writs that we found in MS 33 and 39 can be found in this register in pretty much the same order as in those manuscripts (granted how much is missing the proportions are particularly problematic): Right (9%), Ecclesiastical (19%), Rights in land (9%), Debt, Annuity, Mesne, Warranty of charter, Covenant (11%), Wardship, Dower (13%), Novel disseisin (13%), Entry (11%), Assizes (6%), Miscellaneous (8%). If one wants to speculate about what might have been on the lost quires, we note that in addition to the quire that is missing at the beginning, there are approximately two quires missing before Rights in land, and one quire and five folios before Entry. Since MS 33 and 39 have different things in these places, certainty is not possible, but the statement in the previous paragraph that waste, replevin, trespass, crime, account, and mort d’ancestor could have been on the missing quires seems correct. We can be less sure about formedon; it may not have been there at all. We argue in the Introduction that this manuscript may have been made for an ecclesiastic or a religious house. We also argue that it is not a manuscript that would have been of particular use to a professional lawyer, at least not one who had regular dealings with the central royal courts. The contents of this register, even if we imagine what might have been included in the missing parts, support that argument. |