Click on image for more information |

| The Harvard Law School’s Collection of Medieval English Statute Books and Registers of Writs: A Catalogue |

by Charles Donahue, Jr. |

Paul A. Freund Professor of Law, Harvard Law School |

with the assistance of Devon Coleman |

Private Scholar, Chapel Hill, North Carolina |

PREFACE

|

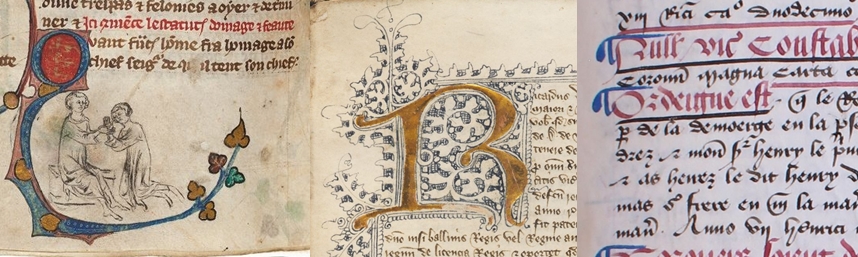

The Harvard Law School Library holds a large collection of English medieval manuscript statute books and registers of writs. Numerous medieval manuscripts of both types of maunscripts survive. Their interest lies in the fact that no two of them are alike. Rather, each seems to have been made up to serve the needs and interests of the person who had them made. Many of them contain matter that does not fit into their general category. Either, for example, may contain brief treatises on pleading; some may contain pieces of Novae Narrationes. The selection of writs or statutes may be standard or quite idiosyncratic. Most of them seem to have been made for practicing lawyers or administrators (though this seems to be less true of the statute books than it is of the registers of writs). Some are quite handsomely laid out and illustrated; some are not. Modern scholarship has had a tendency to ignore these manuscripts.1 There are a very large number of them. Their texts of standard items are, of course, not so reliable as what may be found the printed Statutes of the Realm (S.R.), in Hall’s edition of Early Registers of Writs, or even in the sixteenth-century printing of ‘the’ Register of Writs. They do, however, provide an interesting insight into what lawyers and administratrors in a given period thought might be useful and into what non-lawyers wanted to preserve and/or display. 1. See, however, Rosemarie McGerr, A Lancastrian Mirror for Princes: The Yale Law School New Statutes of England (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011), with references; Don C. Skemer, ‘Reading the Law: Statute Books and the Private Transmission of Legal Knowledge in Late Medieval England’, in Learning the Law: Teaching and the Transmission of law in England, 1150-1900, Jonathan A. Bush and Alain Wijffels ed. (London: Hambledon Press, 1999) 113–131. To make these books useful to scholars, then, what seems to be called for is not an edition of their texts, except in the cases where there is no modern edition of the text (e.g., the De bastardia in HLS MS 24, 24b, 33, 39, 80), but, rather, much more comprehensive lists of their contents than is normally available in library or even in manuscript catalogues. The Ames Foundation is undertaking this with the Harvard collection, taking it as a sample, perhaps an unbiased sample, of such books.2 2. We are not, of course, speaking of a random sample that would satisfy a statistician. It is probably, however, an unbiased sample of what was available on the private market from the time of George Dunn in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, whose entire collection we have, up until the present day. We have made some progress. We now have digital images of all 58 such manuscripts in the HLL collection, all of which are available in the Harvard University Library’s page delivery service, which is known as ‘Mirador’. One of them is simply a single sheet of Magna Carta (HLS MS 172). Seventeen of them are principally registers of writs, including one that is a register of judicial writs. Two of these contain tracts, and one has a single sheet of tracts folded into it. Thirty-eight of them are principally statute-books, six of which also contain registers of writs, and 32 of which contain items that are not in S.R. A final manuscript (HLS MS 193), though classed as a register of writs, is not a register of writs, at least as that term is normally understood, but a collection of some writs and extracts from treatises, but principally extracts from Year Books, designed to illustrate ‘placita personalia’. The Ames Foundation has compiled preliminary descriptions of 57 of these manuscripts. We have not yet tackled HLS MS 172, the single sheet of Magna Carta. Some of the ‘preliminary’ descriptions are still quite preliminary. When a full description is done, the metadata in the margin of Mirador is eventually be changed to pick up the brief descriptions of the items in the manuscripts, and the HOLLIS cataloguing corrected where it is in error. There is, however, some delay before this happens. We would welcome any help or suggestions. They may be sent by email. The Table of Contents provides links to: (1) The three summary tables that we have prepared, the first of which lists all the statutes that are in S.R. that are found in all the manuscripts and comments generally on the statutes so found, the second of which organizes the writs in the registers of writs into groups and provides references to where the groups may be found in the manuscripts, and the third of which lists all the items that we have so far found in the collection that are not statutes that are printed in S.R. or writs in a register of writs. This includes all the treatises and tracts, of which there are more than fifty. (2) The 57 preliminary descriptions that the Ames Foundation has prepared, with links to the online images. An introduction to the list of descriptions explains more fully what we did in the descriptions and provides fuller linked lists of the descriptions. (3) A list of all 58 manuscripts with their HOLLIS description, a brief note, and links to where the manuscripts may be found online. (Multiple links to the online images are also found in the Ames descriptions.) This list includes Hall’s dating of the registers of writs, which is sometimes revised in our descriptions. (4) The search engines, of which we offer three: the first searches all the text fields in the descriptions; the second is specific to the summary table of statutes, and the third is specific to the summary table of writs. A table of abbreviations and a bibliography are, as they say, ‘under construction’. The web pages are optimized for Firefox. We are not aware of any of the standard browsers in which they do not work, and would appreciate learning of any difficulties that users encounter with other browsers (email). There are many links on the web pages shown in gray. The difference in color is not visible on all hand-held devices but they show in blue if you hover over them. The cooperation of the HLL staff in the creation of this catalogue has been simply extraordinary. While many have helped, we would like to acknowledge particularly the assistance of Karen Beck, Stephen Chapman, and Mary Pearson. |